Christmas Eve and the Twelve Days

BY

CLEMENT A. MILES

An excerpt from

CHRISTMAS IN RITUAL AND TRADITION, CHRISTIAN AND PAGAN

1912

Introduction

The celebration of Christmas Eve and the Twelve Days has deep roots that span across various cultures and countries, weaving a rich tapestry of traditions and customs that have evolved over centuries. While Christmas itself is widely recognized as the commemoration of the birth of Jesus Christ, the observance of Christmas Eve and the Twelve Days extends beyond religious significance to encompass a blend of cultural, historical, and folkloric elements.

The origins of Christmas Eve can be traced back to a combination of Christian and pagan traditions. In Christian theology, Christmas Eve marks the evening before the nativity of Jesus, a time when many believers come together for special church services and festive gatherings. However, the observance of the night before Christmas also draws inspiration from pre-Christian winter solstice celebrations, where communities engaged in rituals to welcome the return of light and warmth during the darkest days of the year.

The Twelve Days of Christmas, on the other hand, find their roots in various cultural and religious practices. This period traditionally begins on December 25th and concludes on January 5th, culminating in the celebration of Epiphany on January 6th. Different cultures have assigned different meanings and customs to each of the twelve days, often incorporating elements of feasting, gift-giving, and symbolic rituals.

Across countries, the traditions associated with Christmas Eve and the Twelve Days vary widely. In some regions, Christmas Eve is marked by festive meals and the exchange of gifts, while in others, it is a time for solemn religious observances. The Twelve Days may be celebrated with feasts, music, and merriment, with each day holding its unique significance.

From the Yule celebrations of Norse and Germanic cultures to the Feast of Epiphany in Western Christianity, the ancient origins of Christmas Eve and the Twelve Days reflect the diverse ways in which people have come together to honor the winter season, express gratitude, and celebrate the themes of light, renewal, and community. As these traditions have traversed through time and geography, they continue to evolve, creating a global mosaic of festive customs that bring people together in joyous celebration.

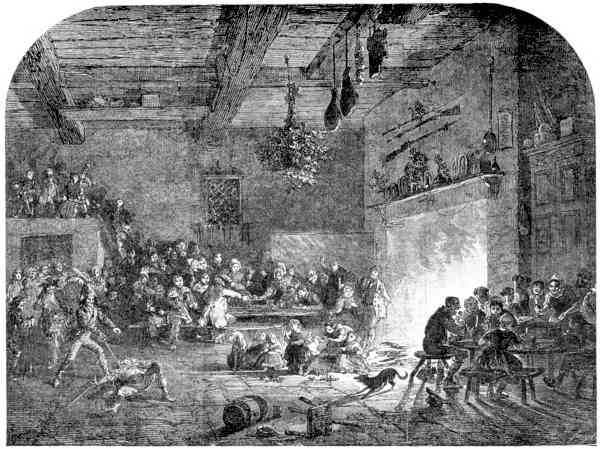

Christmas Eve in Devonshire — The Mummers coming in.

Christmas Eve and the Twelve Days

Christmas Eve.

Christmas in the narrowest sense must be reckoned as beginning on the evening of December 24. Though Christmas Eve is not much observed in modern England, throughout the rest of Europe its importance so far as popular customs are concerned is far greater than that of the Day itself. Then in Germany the Christmas-tree is manifested in its glory; then, as in the England of the past, the Yule log is solemnly lighted in many lands; then often the most distinctive Christmas meal takes place.

We shall consider these and other institutions later; though they appear first on Christmas Eve, they belong more or less to the Twelve Days as a whole. Let us look first at the supernatural visitors, mimed by human beings, who delight the minds of children, especially in Germany, on the evening of December 24, and at the beliefs that hang around this most solemn night of the year.

First of all, the activities of St. Nicholas are not confined to his own festival; he often appears on Christmas Eve. We have already seen how he is attended by various companions, including Christ Himself, and how he comes now vested as a bishop, now as a masked and shaggy figure. The names and attributes of the Christmas and Advent visitors are rather confused, but on the whole it may be said that in Protestant north Germany the episcopal St. Nicholas and his Eve have been replaced by Christmas Eve and the Christ Child, while the name Klas has become attached to various unsaintly forms appearing at or shortly before Christmas.

We can trace a deliberate substitution of the Christ Child for St. Nicholas as the bringer of gifts. In the early seventeenth century a Protestant pastor is found complaining that parents put presents in their children's beds and tell them that St. Nicholas has brought them. “This,” he says, “is a bad custom, because it points children to the saint, while yet we know that not St. Nicholas but the holy Christ Child gives us all good things for body and soul, and He alone it is whom we ought to call upon.”

The ways in which the figure, or at all events the name, of Christ Himself, is introduced into German Christmas customs, are often surprising. The Christ Child, “Christkind,” so familiar to German children, has now become a sort of mythical figure, a product of sentiment and imagination working so freely as almost to forget the sacred character of the original. Christkind bears little resemblance to the Infant of Bethlehem; he is quite a tall child, and is often represented by a girl dressed in white, with long fair hair. He hovers, indeed, between the character of the Divine Infant and that of an angel, and is regarded more as a kind of good fairy than as anything else.

In Alsace the girl who represents Christkind has her face “made up” with flour, wears a crown of gold paper with lighted candles in it—a parallel to the headgear of the Swedish Lussi; in one hand she holds a silver bell, in the other, a basket of sweetmeats. She is followed by the terrible Hans Trapp, dressed in a bearskin, with blackened face, long beard, and threatening rod. He “goes for” the naughty children, who are only saved by the intercession of Christkind.

In the Mittelmark the name of de hêle (holy) Christ is strangely given to a skin- or straw-clad man, elsewhere called Knecht Ruprecht, Klas, or Joseph. In the Ruppin district a man dresses up in white with ribbons, carries a large pouch, and is called Christmann or Christpuppe. He is accompanied by a Schimmelreiter and by other fellows who are attired as women, have blackened faces, and are named Feien (we may see in them a likeness to the Kalends maskers condemned by the early Church). The procession goes round from house to house. The Schimmelreiter as he enters has to jump over a chair; this done, the Christpuppe is admitted. The girls present begin to sing, and the Schimmelreiter dances with one of them. Meanwhile the Christpuppe makes the children repeat some verse of Scripture or a hymn; if they know it well, he rewards them with gingerbreads from his wallet; if not, he beats them with a bundle filled with ashes. Then both he and the Schimmelreiter dance and pass on. Only when they are gone are the Feien allowed to enter; they jump wildly about and frighten the children.

Knecht Ruprecht, to whom allusion has already been made, is a prominent figure in the German Christmas. On Christmas Eve in the north he goes about clad in skins or straw and examines children; if they can say their prayers perfectly he rewards them with apples, nuts and gingerbreads; if not, he punishes them. In the Mittelmark, as we have seen, a personage corresponding to him is sometimes called “the holy Christ”; in Mecklenburg he is “rû Klas” (rough Nicholas—note his identification with the saint); in Brunswick, Hanover, and Holstein “Klas,” “Klawes,” “Klas Bûr” and “Bullerklas”; and in Silesia “Joseph.” Sometimes he wears bells and carries a long staff with a bag of ashes at the end—hence the name “Aschenklas” occasionally given to him. An ingenious theory connects this aspect of him with the polaznik of the Slavs, who on Christmas Day in Crivoscian farms goes to the hearth, takes up the ashes of the Yule log and dashes them against the cauldron-hook above so that sparks fly. As for the name “Ruprecht” the older mythologists interpreted it as meaning “shining with glory,” hruodperaht, and identified its owner with the god Woden. Dr. Tille, however, regards him as dating only from the seventeenth century. It can hardly be said that any satisfactory account has as yet been given of the origins of this personage, or of his relation to St. Nicholas, Pelzmärte, and monstrous creatures like the Klapperbock.

In the south-western part of Lower Austria, both St. Nicholas—a proper bishop with mitre, staff, and ring—and Ruprecht appear on Christmas Eve, and there is quite an elaborate ceremonial. The children welcome the saint with a hymn; then he goes to a table and makes each child repeat a prayer and show his lesson-books. Meanwhile Ruprecht in a hide, with glowing eyes and a long red tongue, stands at the door to overawe the young people. Each child next kneels before the saint and kisses his ring, whereupon Nicholas bids him put his shoes out-of-doors and look in them when the clock strikes ten. After this the saint lays on the table a rod dipped in lime, solemnly blesses the children, sprinkling them with holy water, and noiselessly departs. The children steal out into the garden, clear a space in the snow, and set out their shoes; when the last stroke of ten has sounded they find them filled with nuts and apples and all kinds of sweet things.

In the Troppau district of Austrian Silesia, three figures go round on Christmas Eve—Christkindel, the archangel Gabriel, and St. Peter—and perform a little play before the presents they bring are given. Christkindel announces that he has gifts for the good children, but the bad shall feel the rod. St. Peter complains of the naughtiness of the youngsters: they play about in the streets instead of going straight to school; they tear up their lesson-books and do many other wicked things. However, the children's mother pleads for them, and St. Peter relents and gives out the presents.

In the Erzgebirge appear St. Peter and Ruprecht, who is clad in skin and straw, has a mask over his face, a rod, a chain round his body, and a sack with apples, nuts, and other gifts; and a somewhat similar performance is gone through.

If we go as far east as Russia we find a parallel to the girl Christkind in Kolyáda, a white-robed maiden driven about in a sledge from house to house on Christmas Eve. The young people who attended her sang carols, and presents were given them in return. Kolyáda is the name for Christmas and appears to be derived from Kalendae, which probably entered the Slavonic languages by way of Byzantium. The maiden is one of those beings who, like the Italian Befana, have taken their names from the festival at which they appear.

No time in all the Twelve Nights and Days is so charged with the supernatural as Christmas Eve. Doubtless this is due to the fact that the Church has hallowed the night of December 24-5 above all others in the year. It was to the shepherds keeping watch over their flocks by night that, according to the Third Evangelist, came the angelic message of the Birth, and in harmony with this is the unique Midnight Mass of the Roman Church, lending a peculiar sanctity to the hour of its celebration. And yet many of the beliefs associated with this night show a large admixture of paganism.

First, there is the idea that at midnight on Christmas Eve animals have the power of speech. This superstition exists in various parts of Europe, and no one can hear the beasts talk with impunity. The idea has given rise to some curious and rather grim tales. Here is one from Brittany:—

“Once upon a time there was a woman who starved her cat and dog. At midnight on Christmas Eve she heard the dog say to the cat, ‘It is quite time we lost our mistress; she is a regular miser. To-night burglars are coming to steal her money; and if she cries out they will break her head.’ ‘’Twill be a good deed,’ the cat replied. The woman in terror got up to go to a neighbour's house; as she went out the burglars opened the door, and when she shouted for help they broke her head.”

Again a story is told of a farm servant in the German Alps who did not believe that the beasts could speak, and hid in a stable on Christmas Eve to learn what went on. At midnight he heard surprising things. “We shall have hard work to do this day week,” said one horse. “Yes, the farmer's servant is heavy,” answered the other. “And the way to the churchyard is long and steep,” said the first. The servant was buried that day week.

It may well have been the traditional association of the ox and ass with the Nativity that fixed this superstition to Christmas Eve, but the conception of the talking animals is probably pagan.

Related to this idea, but more Christian in form, is the belief that at midnight all cattle rise in their stalls or kneel and adore the new-born King. Readers of Mr. Hardy's “Tess” will remember how this is brought into a delightful story told by a Wessex peasant. The idea is widespread in England and on the Continent, and has reached even the North American Indians. Howison, in his “Sketches of Upper Canada,” relates that an Indian told him that “on Christmas night all deer kneel and look up to Great Spirit.” A somewhat similar belief about bees was held in the north of England: they were said to assemble on Christmas Eve and hum a Christmas hymn. Bees seem in folk-lore in general to be specially near to humanity in their feelings.

It is a widespread idea that at midnight on Christmas Eve all water turns to wine. A Guernsey woman once determined to test this; at midnight she drew a bucket from the well. Then came a voice:—

“Toute l'eau se tourne en vin,

Et tu es proche de ta fin.”

She fell down with a mortal disease, and died before the end of the year. In Sark the superstition is that the water in streams and wells turns into blood, and if you go to look you will die within the year.

There is also a French belief that on Christmas Eve, while the genealogy of Christ is being chanted at the Midnight Mass, hidden treasures are revealed. In Russia all sorts of buried treasures are supposed to be revealed on the evenings between Christmas and the Epiphany, and on the eves of these festivals the heavens are opened, and the waters of springs and rivers turn into wine.

Another instance of the supernatural character of the night is found in a Breton story of a blacksmith who went on working after the sacring bell had rung at the Midnight Mass. To him came a tall, stooping man with a scythe, who begged him to put in a nail. He did so; and the visitor in return bade him send for a priest, for this work would be his last. The figure disappeared, the blacksmith felt his limbs fail him, and at cock-crow he died. He had mended the scythe of the Ankou—Death the reaper.

In the Scandinavian countries simple folk have a vivid sense of the nearness of the supernatural on Christmas Eve. On Yule night no one should go out, for he may meet uncanny beings of all kinds. In Sweden the Trolls are believed to celebrate Christmas Eve with dancing and revelry. “On the heaths witches and little Trolls ride, one on a wolf, another on a broom or a shovel, to their assemblies, where they dance under their stones.... In the mount are then to be heard mirth and music, dancing and drinking. On Christmas morn, during the time between cock-crowing and daybreak, it is highly dangerous to be abroad.”

Christmas Eve is also in Scandinavian folk-belief the time when the dead revisit their old homes, as on All Souls’ Eve in Roman Catholic lands. The living prepare for their coming with mingled dread and desire to make them welcome. When the Christmas Eve festivities are over, and everyone has gone to rest, the parlour is left tidy and adorned, with a great fire burning, candles lighted, the table covered with a festive cloth and plentifully spread with food, and a jug of Yule ale ready. Sometimes before going to bed people wipe the chairs with a clean white towel; in the morning they are wiped again, and, if earth is found, some kinsman, fresh from the grave, has sat there. Consideration for the dead even leads people to prepare a warm bath in the belief that, like living folks, the kinsmen will want a wash before their festal meal. Or again beds were made ready for them while the living slept on straw. Not always is it consciously the dead for whom these preparations are made, sometimes they are said to be for the Trolls and sometimes even for the Saviour and His angels. (We may compare with this Christian idea the Tyrolese custom of leaving some milk for the Christ Child and His Mother at the hour of Midnight Mass, and a Breton practice of leaving food all through Christmas night in case the Virgin should come.)

It is difficult to say how far the other supernatural beings—their name is legion—who in Norway, Sweden, Denmark, and Iceland are believed to come out of their underground hiding-places during the long dark Christmas nights, were originally ghosts of the dead. Twenty years ago many students would have accounted for them all in this way, but the tendency now is strongly against the derivation of all supernatural beings from ancestor-worship. Elves, trolls, dwarfs, witches, and other uncanny folk—the beliefs about their Christmas doings are too many to be treated here; readers of Danish will find a long and very interesting chapter on this subject in Dr. Feilberg's “Jul.” I may mention just one familiar figure of the Scandinavian Yule, Tomte Gubbe, a sort of genius of the house corresponding very much to the “drudging goblin” of Milton's “L'Allegro,” for whom the cream-bowl must be duly set. He may perhaps be the spirit of the founder of the family. At all events on Christmas Eve Yule porridge and new milk are set out for him, sometimes with other things, such as a suit of small clothes, spirits, or even tobacco. Thus must his goodwill be won for the coming year.

In one part of Norway it used to be believed that on Christmas Eve, at rare intervals, the old Norse gods made war on Christians, coming down from the mountains with great blasts of wind and wild shouts, and carrying off any human being who might be about. In one place the memory of such a visitation was preserved in the nineteenth century. The people were preparing for their festivities, when suddenly from the mountains came the warning sounds. “In a second the air became black, peals of thunder echoed among the hills, lightning danced about the buildings, and the inhabitants in the darkened rooms heard the clatter of hoofs and the weird shrieks of the hosts of the gods.”

The Scandinavian countries, Protestant though they are, have retained many of the outward forms of Catholicism, and the sign of the cross is often used as a protection against uncanny visitors. The cross—perhaps the symbol was originally Thor's hammer—is marked with chalk or tar or fire upon doors and gates, is formed of straw or other material and put in stables and cowhouses, or is smeared with the remains of the Yule candle on the udders of the beasts—it is in fact displayed at every point open to attack by a spirit of darkness.

Christmas Eve is in Germany a time for auguries. Some of the methods already noted on other days are practised upon it—for instance the pouring of molten lead into water, the flinging of shoes, the pulling out of pieces of wood, and the floating of nutshells—and there are various others which it might be tedious to describe.

Among the southern Slavs if a girl wants to know what sort of husband she will get, she covers the table on Christmas Eve, puts on it a white loaf, a plate, and a knife, spoon, and fork, and goes to bed. At midnight the spirit of her future husband will appear and fling the knife at her. If it falls without injuring her she will get a good husband and be happy, but if she is hurt she will die early. There is a similar mode of divination for a young fellow. On Christmas Eve, when everybody else has gone to church, he must, naked and in darkness, sift ashes through a sieve. His future bride will then appear, pull him thrice by the nose, and go away.

In eastern Europe Christmas, and especially Christmas Eve, is the time for the singing of carols called in Russian Kolyádki, and in other Slav countries by similar names derived from Kalendae. More often than not these are without connection with the Nativity; sometimes they have a Christian form and tell of the doings of God, the Virgin and the saints, but frequently they are of an entirely secular or even pagan character. Into some the sun, moon, and stars and other natural objects are introduced, and they seem to be based on myths to which a Christian appearance has been given by a sprinkling of names of holy persons of the Church. Here for instance is a fragment from a Carpathian song:—

“A golden plough goes ploughing,

And behind that plough is the Lord Himself.

The holy Peter helps Him to drive,

And the Mother of God carries the seed corn,

Carries the seed corn, prays to the Lord God,

‘Make, O Lord, the strong wheat to grow,

The strong wheat and the vigorous corn!

The stalks then shall be like reeds!’”

Often they contain wishes for the prosperity of the household and end with the words, “for many years, for many years.” The Roumanian songs are frequently very long, and a typical, oft-recurring refrain is:—

“This evening is a great evening,

White flowers;

Great evening of Christmas,

White flowers.”

Sometimes they are ballads of the national life.

In Russia a carol beginning “Glory be to God in heaven, Glory!” and calling down blessings on the Tsar and his people, is one of the most prominent among the Kolyádki, and opens the singing of the songs called Podblyudnuiya. “At the Christmas festival a table is covered with a cloth, and on it is set a dish or bowl (blyudo) containing water. The young people drop rings or other trinkets into the dish, which is afterwards covered with a cloth, and then the Podblyudnuiya Songs commence. At the end of each song one of the trinkets is drawn at random, and its owner deduces an omen from the nature of the words which have just been sung.”

The Twelve Days.

Whatever the limits fixed for the beginning and end of the Christmas festival, its core is always the period between Christmas Eve and the Epiphany—the “Twelve Days.” A cycle of feasts falls within this time, and the customs peculiar to each day will be treated in calendarial order. First, however, it will be well to glance at the character of the Twelve Days as a whole, and at the superstitions which hang about the season. So many are these superstitions, so “bewitched” is the time, that the older mythologists not unnaturally saw in it a Teutonic festal season, dating from pre-Christian days. In point of fact it appears to be simply a creation of the Church, a natural linking together of Christmas and Epiphany. It is first mentioned as a festal tide by the eastern Father, Ephraem Syrus, at the end of the fourth century, and was declared to be such by the western Council of Tours in 567.

While Christmas Eve is the night par excellence of the supernatural, the whole season of the Twelve Days is charged with it. It is hard to see whence Shakespeare could have got the idea which he puts into the mouth of Marcellus in “Hamlet”:—

“Some say that ever ‘gainst that season comes

Wherein our Saviour's birth is celebrated,

The bird of dawning singeth all night long;

And then, they say, no spirit dare stir abroad;

The nights are wholesome; then no planets strike,

No fairy takes, nor witch hath power to charm,

So hallow'd and so gracious is the time.”

Against this is the fact that in folk-lore Christmas is a quite peculiarly uncanny time. Not unnatural is it that at this midwinter season of darkness, howling winds, and raging storms, men should have thought to see and hear the mysterious shapes and voices of dread beings whom the living shun.

Throughout the Teutonic world one finds the belief in a “raging host” or “wild hunt” or spirits, rushing howling through the air on stormy nights. In North Devon its name is “Yeth (heathen) hounds”; elsewhere in the west of England it is called the “Wish hounds.” It is the train of the unhappy souls of those who died unbaptized, or by violent hands, or under a curse, and often Woden is their leader. At least since the seventeenth century this “raging host” (das wüthende Heer) has been particularly associated with Christmas in German folk-lore, and in Iceland it goes by the name of the “Yule host.”

In Guernsey the powers of darkness are supposed to be more than usually active between St. Thomas's Day and New Year's Eve, and it is dangerous to be out after nightfall. People are led astray then by Will o’ the Wisp, or are preceded or followed by large black dogs, or find their path beset by white rabbits that go hopping along just under their feet.

In England there are signs that supernatural visitors were formerly looked for during the Twelve Days. First there was a custom of cleansing the house and its implements with peculiar care. In Shropshire, for instance, “the pewter and brazen vessels had to be made so bright that the maids could see to put their caps on in them—otherwise the fairies would pinch them, but if all was perfect, the worker would find a coin in her shoe.” Again in Shropshire special care was taken to put away any suds or “back-lee” for washing purposes, and no spinning might be done during the Twelve Days. It was said elsewhere that if any flax were left on the distaff, the Devil would come and cut it.

The prohibition of spinning may be due to the Church's hallowing of the season and the idea that all work then was wrong. This churchly hallowing may lie also at the root of the Danish tradition that from Christmas till New Year's Day nothing that runs round should be set in motion, and of the German idea that no thrashing must be done during the Twelve Days, or all the corn within hearing will spoil. The expectation of uncanny visitors in the English traditions calls, however, for special attention; it is perhaps because of their coming that the house must be left spotlessly clean and with as little as possible about on which they can work mischief. Though I know of no distinct English belief in the return of the family dead at Christmas, it may be that the fairies expected in Shropshire were originally ancestral ghosts. Such a derivation of the elves and brownies that haunt the hearth is very probable.

The belief about the Devil cutting flax left on the distaff links the English superstitions to the mysterious Frau with various names, who in Germany is supposed to go her rounds during the Twelve Nights. She has a special relation to spinning, often punishing girls who leave their flax unspun. In central Germany and in parts of Austria she is called Frau Holle or Holda, in southern Germany and Tyrol Frau Berchta or Perchta, in the north down to the Harz Mountains Frau Freen or Frick, or Fru Gode or Fru Harke, and there are other names too. Attempts have been made to dispute her claim to the rank of an old Teutonic goddess and to prove her a creation of the Middle Ages, a representative of the crowd of ghosts supposed to be specially near to the living at Christmastide. It is questionable whether she can be thus explained away, and at the back of the varying names, and much overlaid no doubt with later superstitions, there may be a traditional goddess corresponding to that old divinity Frigg to whom we owe the name of Friday. The connection of Frick with Frigg is very probable, and Frick shares characteristics with the other Frauen.

All are connected with spinning and spinsters (in the literal sense). Fru Frick or Freen in the Uckermark and the northern Harz permits no spinning during the time when she goes her rounds, and if there are lazy spinsters she soils the unspun flax on their distaff. In like manner do Holda, Harke, Berchta, and Gode punish lazy girls.

The characters of the Frauen can best be shown by the things told of them in different regions. They are more dreaded than loved, but if severe in their chastisements they are also generous in rewarding those who do them service.

Frau Gaude (also called Gode, Gaue, or Wode) is said in Mecklenburg to love to drive through the village streets on the Twelve Nights with a train of dogs. Wherever she finds a street-door open she sends a little dog in. Next morning he wags his tail at the inmates and whines, and will not be driven away. If killed, he turns into a stone by day; this, though it may be thrown away, always returns and is a dog again by night. All through the year he whines and brings ill luck upon the house; so people are careful to keep their street-doors shut during the Twelve Nights.

Good luck, however, befalls those who do Frau Gaude a service. A man who put a new pole to her carriage was brilliantly repaid—the chips that fell from the pole turned to glittering gold. Similar stories of golden chips are told about Holda and Berchta.

A train of dogs belongs not only to Frau Gaude but also to Frau Harke; with these howling beasts they go raging through the air by night. The Frauen in certain aspects are, indeed, the leaders of the “Wild Host.”

Holda and Perchta, as some strange stories show, are the guides and guardians of the heimchen or souls of children who have died unbaptized. In the valley of the Saale, so runs a tale, Perchta, queen of the heimchen, had her dwelling of old, and at her command the children watered the fields, while she worked with her plough. But the people of the place were ungrateful, and she resolved to leave their land. One night a ferryman beheld on the bank of the Saale a tall, stately lady with a crowd of weeping children. She demanded to be ferried across, and the children dragged a plough into the boat, crying bitterly. As a reward for the ferrying, Perchta, mending her plough, pointed to the chips. The man grumblingly took three, and in the morning they had turned to gold-pieces.

Holda, whose name means “the kindly one,” is the most friendly of the Frauen. In Saxony she brings rewards for diligent spinsters, and on every New Year's Eve, between nine and ten o'clock, she drives in a carriage full of presents through villages where respect has been shown to her. At the crack of her whip the people come out to receive her gifts. In Hesse and Thuringia she is imagined as a beautiful woman clad in white with long golden hair, and, when it snows hard, people say, “Frau Holle is shaking her featherbed.”

More of a bugbear on the whole is Berchte or Perchte (the name is variously spelt). She is particularly connected with the Eve of the Epiphany, and it is possible that her name comes from the old German giper(c)hta Na(c)ht, the bright or shining night, referring to the manifestation of Christ's glory. In Carinthia the Epiphany is still called Berchtentag.

Berchte is sometimes a bogey to frighten children. In the mountains round Traunstein children are told on Epiphany Eve that if they are naughty she will come and cut their stomachs open. In Upper Austria the girls must finish their spinning by Christmas; if Frau Berch finds flax still on their distaffs she will be angered and send them bad luck.

In the Orlagau (between the Saale and the Orle) on the night before Twelfth Day, Perchta examines the spinning-rooms and brings the spinners empty reels with directions to spin them full within a very brief time; if this is not done she punishes them by tangling and befouling the flax. She also cuts open the body of any one who has not eaten zemmede (fasting fare made of flour and milk and water) that day, takes out any other food he has had, fills the empty space with straw and bricks, and sews him up again. And yet, as we have seen, she has a kindly side—at any rate she rewards those who serve her—and in Styria at Christmas she even plays the part of Santa Klaus, hearing children repeat their prayers and rewarding them with nuts and apples.

There is a charming Tyrolese story about her. At midnight on Epiphany Eve a peasant—not too sober—suddenly heard behind him “a sound of many voices, which came on nearer and nearer, and then the Berchtl, in her white clothing, her broken ploughshare in her hand, and all her train of little people, swept clattering and chattering close past him. The least was the last, and it wore a long shirt which got in the way of its little bare feet, and kept tripping it up. The peasant had sense enough left to feel compassion, so he took his garter off and bound it for a girdle round the infant, and then set it again on its way. When the Berchtl saw what he had done, she turned back and thanked him, and told him that in return for his compassion his children should never come to want.”

In Tyrol, by the way, it is often said that the Perchtl is Pontius Pilate's wife, Procula. In the Italian dialects of south Tyrol the German Frau Berchta has been turned into la donna Berta. If one goes further south, into Italy itself, one meets with a similar being, the Befana, whose name is plainly nothing but a corruption of Epiphania. She is so distinctly a part of the Epiphany festival that we may leave her to be considered later.

Of all supernatural Christmas visitors, the most vividly realized and believed in at the present day are probably the Greek Kallikantzaroi or Karkantzaroi. They are the terror of the Greek peasant during the Twelve Days; in the soil of his imagination they flourish luxuriantly, and to him they are a very real and living nuisance.

Traditions about the Kallikantzaroi vary from region to region, but in general they are half-animal, half-human monsters, black, hairy, with huge heads, glaring red eyes, goats’ or asses’ ears, blood-red tongues hanging out, ferocious tusks, monkeys’ arms, and long curved nails, and commonly they have the foot of some beast. “From dawn till sunset they hide themselves in dark and dank places ... but at night they issue forth and run wildly to and fro, rending and crushing those who cross their path. Destruction and waste, greed and lust mark their course.” When a house is not prepared against their coming, “by chimney and door alike they swarm in, and make havoc of the home; in sheer wanton mischief they overturn and break all the furniture, devour the Christmas pork, befoul all the water and wine and food which remains, and leave the occupants half dead with fright or violence.” Many like or far worse pranks do they play, until at the crowing of the third cock they get them away to their dens. The signal for their final departure does not come until the Epiphany, when the “Blessing of the Waters” takes place. Some of the hallowed water is put into vessels, and with these and with incense the priests sometimes make a round of the village, sprinkling the people and their houses. The fear of the Kallikantzaroi at this purification is expressed in the following lines:—

“Quick, begone! we must begone,

Here comes the pot-bellied priest,

With his censer in his hand

And his sprinkling-vessel too;

He has purified the streams

And he has polluted us.”

Besides this ecclesiastical purification there are various Christian precautions against the Kallikantzaroi—e.g., to mark the house-door with a black cross on Christmas Eve, the burning of incense and the invocation of the Trinity—and a number of other means of aversion: the lighting of the Yule log, the burning of something that smells strong, and—perhaps as a peace-offering—the hanging of pork-bones, sweetmeats, or sausages in the chimney.

Just as men are sometimes believed to become vampires temporarily during their lifetime, so, according to one stream of tradition, do living men become Kallikantzaroi. In Greece children born at Christmas are thought likely to have this objectionable characteristic as a punishment for their mothers’ sin in bearing them at a time sacred to the Mother of God. In Macedonia people who have a “light” guardian angel undergo the hideous transformation.

Many attempts have been made to account for the Kallikantzaroi. Perhaps the most plausible explanation of the outward form, at least, of the uncanny creatures, is the theory connecting them with the masquerades that formed part of the winter festival of Dionysus and are still to be found in Greece at Christmastide. The hideous bestial shapes, the noise and riot, may well have seemed demoniacal to simple people slightly “elevated,” perhaps, by Christmas feasting, while the human nature of the maskers was not altogether forgotten. Another theory of an even more prosaic character has been propounded—“that the Kallikantzaroi are nothing more than established nightmares, limited like indigestion to the twelve days of feasting. This view is 246taken by Allatius, who says that a Kallikantzaros has all the characteristics of nightmare, rampaging abroad and jumping on men's shoulders, then leaving them half senseless on the ground.”

Such theories are ingenious and suggestive, and may be true to a certain degree, but they hardly cover all the facts. It is possible that the Kallikantzaroi may have some connection with the departed; they certainly appear akin to the modern Greek and Slavonic vampire, “a corpse imbued with a kind of half-life,” and with eyes gleaming like live coals. They are, however, even more closely related to the werewolf, a man who is supposed to change into a wolf and go about ravening. It is to be noted that “man-wolves” (λυκανθρωποι) is the very name given to the Kallikantzaroi in southern Greece, and that the word Kallikantzaros itself has been conjecturally derived by Bernhard Schmidt from two Turkish words meaning “black” and “werewolf.” The connection between Christmas and werewolves is not confined to Greece. According to a belief not yet extinct in the north and east of Germany, even where the real animals have long ago been extirpated, children born during the Twelve Nights become werewolves, while in Livonia and Poland that period is the special season for the werewolf's ravenings.

Perhaps on no question connected with primitive religion is there more uncertainty than on the ideas of early man about the nature of animals and their relation to himself and the world. When we meet with half-animal, half-human beings we must be prepared to find much that is obscure.

With the Kallikantzaroi may be compared some goblins of the Celtic imagination; especially like is the Manx Fynnodderee (lit. “the hairy-dun one”), “something between a man and a beast, being covered with black shaggy hair and having fiery eyes,” and prodigiously strong. The Russian Domovy or house-spirit is also a hirsute creature, and the Russian Ljeschi, goat-footed woodland sprites, are, like the Kallikantzaroi, supposed to be got rid of by the “Blessing of the Waters” at the Epiphany. Some of the monstrous German figures already dealt with here bear strong resemblances to the Greek demons. And, of course, on Greek ground one cannot help thinking of Pan and the Satyrs and Centaurs.