-

"I got all my boyhood in vanilla winter waves around the kitchen stove."

Jack Kerouac

Stories

Dickens’s “A Christmas Tree” wanders through the ornaments of childhood memory, using the Christmas tree as a symbolic ladder from toys to tales to ghostly imaginings and finally to spiritual reflection. It’s a dreamy, nostalgic essay that captures how Christmas gathers together wonder, fear, and hope across a lifetime.

Dickens meditates on how the meaning of Christmas deepens with age, expanding beyond youthful fantasy into a season of remembrance, compassion, and forgiveness. He urges readers to “shut out nothing,” embracing joy and sorrow alike as part of the holiday’s enduring humanity.

A young girl escapes the man-eating witch Baba Yaga using wit, kindness, and two magical objects, a towel that becomes a river and a comb that becomes a forest. It’s a quintessential Slavic fairy tale where humble acts open the door to supernatural protection.

Folkard’s introduction offers a dense and dazzling catalog of the world's floral mythology—an herbal grimoire where every leaf and blossom carries symbolic weight, medical promise, or ancient superstition. At once antiquarian and poetic, it opens the door to a world where plants are not background, but characters: whispered to by witches, consecrated by priests, and feared by those who know too much.

In this sweeping, syncretic account of ancient winter rites, Pringle and Urann trace Christmas’s pagan inheritance with anthropological exuberance, where mistletoe is deadly, boars are solar, and the sun’s return is a matter of mythic urgency. Long before the birth of Christ, Yule was already ablaze with light, feasting, and the longing for resurrection.

Yule-tide in England evolved from Druidic ritual and Celtic mirth into centuries of roaring fires, wassail bowls, and lavish feasts that reached their zenith in the Tudor and Stuart courts, where mistletoe, mummers, and the boar’s head held symbolic sway. Though later tempered by Puritan austerity and modern restraint, England’s Christmas traditions remain steeped in a history of communal revelry, spiritual observance, and enduring seasonal superstition.

Parties

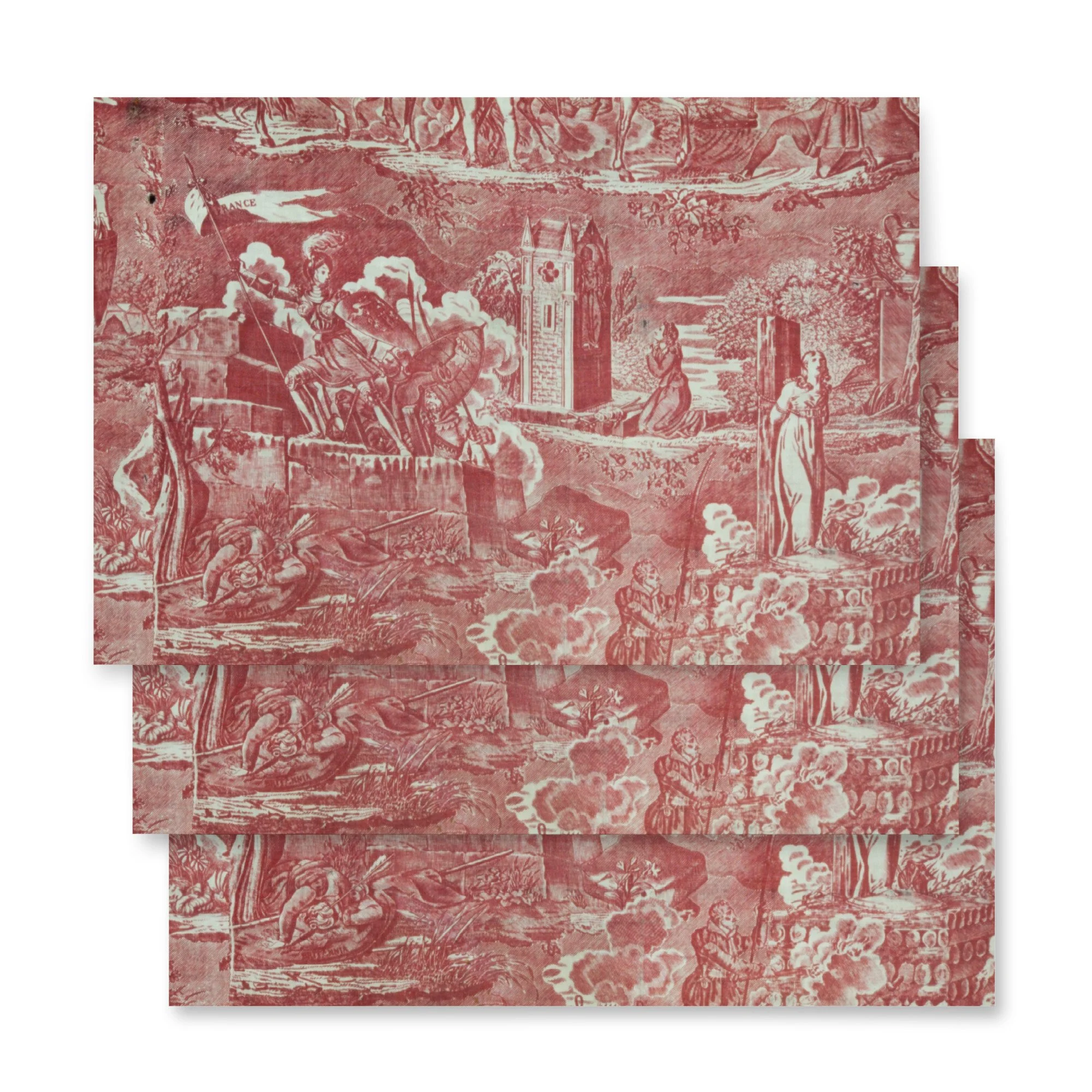

Black and White Christmas

A curated winter collection in stark black and white — woodblock prints, vintage photography, bold type, and folkloric motifs designed for dramatic holiday gifting and décor.

Crafts