The History of the Condition of Women: Europe

But Men Must Work and Women Must Weep, 1883 by Walter Langley

BY

MRS. D. L. CHILD

An excerpt from

THE HISTORY OF THE CONDITION OF WOMEN, IN VARIOUS AGES AND NATIONS

1840

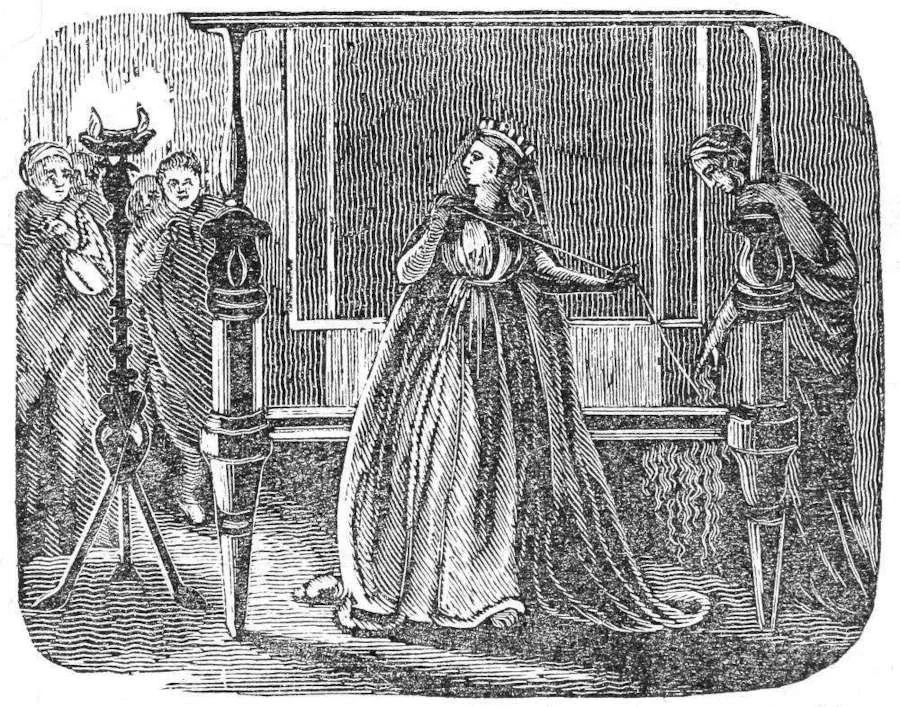

Penelope at her loom.

Plutarch speaks with disapprobation of the Persian manner of treating women; yet the Greeks themselves kept them under very strict discipline. They had distinct apartments, in the highest and most retired part of the house, and among the wealthier classes these rooms were often kept locked and guarded. Women belonging to the royal families were not even allowed to go from one part of the house to the other without permission. When Antigone, in Euripides, obtains her mother’s permission to go on the house-top to view the Argian army, her aged guardian insists upon first searching the passage, lest the profane eyes of a citizen should dishonor her by a glance.

Young girls were more rigorously secluded than married women; yet it was considered highly indecorous for the latter to be seen beyond the door-step, until they were old enough to assume the character of matrons. Menander says:

“You go beyond the married woman’s bounds,

And stand before the hall, which is not fit;

The laws do not permit a free-born bride

Farther than to the outer door to go.”

Maidens were rarely allowed to appear in the presence of men; and never without veils. This covering was probably made of transparent stuff; for Iphigenia speaks of seeing her brother through “the veil’s fine texture.”

Eustathius says, “Women should keep within doors, and there talk.” Thucydides declared that “she was the best woman of whom the least was said, either of good or harm;” according to the Greek proverb it was considered extremely dishonorable to be governed by a female; and Plato rejoiced that he was not born a woman.

In order to prevent assignations, Solon enacted that no wife, or matron, should go from home with more than three garments, or a basket longer than one cubit, or more food than could be purchased for an obolus;[1] or travel in the night-time without a lighted torch carried before her chariot. Lest pride should seek to exhibit itself in a pompous retinue, he ordered that no woman should appear attended by more than one servant, except when she was drunk! On the death of a husband, the oldest son became the guardian of his mother. A woman was incapable of appearing in court without her guardian; therefore the words of the proclamation always were, “We cite —— and her guardian.” No property could be disposed of, either by will or otherwise, without the consent of guardians. Female captives taken in war were not usually treated with any degree of respect or tenderness: thus we find Hecuba complaining that she was chained, like a dog, at the gate of Agamemnon. Alexander the Great formed an honorable exception to this rule, and in his treatment of the royal Persian prisoners imitated the noble example of Cyrus.

Women were not allowed to attend the Olympic games; but this prohibition could not have existed at all periods; for we are told that Cynisca, daughter of Archidamus, king of Sparta, was the first woman who won the prize in the chariot-race at Olympia. Perhaps the Spartan women alone partook of these masculine diversions; those of more feminine habits would probably perceive the propriety of not attending games, where the combatants wrestled without clothing. In commemoration of her victory, Cynisca sent a chariot and four brazen horses, to be dedicated to Olympian Jupiter.

In the earliest ages, Greek women had a right to vote in the public assemblies; but this privilege was taken away from them. They were never allowed to be present at banquets, and it is not supposed that they ever ate in the same apartment with the men.

The restraint of female influence being thus removed, it may be presumed that the outward forms of decency were less scrupulously observed than they would have been under a different system. A fine of one thousand drachmas was imposed upon every woman who appeared in public without clothing; and the necessity of making such a law does not speak well for purity of manners.

That women were not always entirely passive and subservient, appears by the example of Xantippe, so famous for her household eloquence; and by the dispute between Agamemnon and his wife, concerning his wish that she should absent herself from the wedding of her daughter Iphigenia:

Agamemnon. “Without more reasonings, my demands obey!”

Clytemnestra. “By Juno, that o’er Argos bears the sway,

Sooner would wretched Clytemnestra bleed,

Than give consent to so unjust a deed.

Affairs abroad better thy lot become;

’Tis fit that I should manage things at home.”

Themistocles used to say, “My little boy rules Athens; for he governs his mother, and his mother governs me.”

The women of Lemnos, finding themselves slighted for the sake of certain Thracian captives, whose charms conquered their conquerors, resolved upon indiscriminate revenge. They unanimously agreed to put all their male relations to death; and this barbarous plan was carried into execution, with the solitary exception of Hypsipyle, the queen, who spared the life of her father. In consequence of this, the women conspired against her, and soon after drove her from the kingdom.

The most common employments of Grecian women were spinning, weaving, embroidery, making garments, and attending to household avocations. Their embroidery often represented battle-scenes and historical events, which must have required a great deal of time and patience. During the early ages, there seems to have been no difference whatever between the occupations of princesses and women of common rank. Before marriage, Penelope tended her father’s flocks on the mountains of Arcadia; and when she was queen of Ithaca, her son bids her attend to the spindle and the loom, and leave the affairs of the palace to his direction. During the absence of her husband, she was troubled with numerous powerful suitors, whose enmity was greatly to be feared in those turbulent times. She promised to choose one from among them, when she had finished weaving a certain web; but she continually baffled them, by unravelling in the night what she had woven in the day: hence “Penelope’s web” became a proverbial expression for works that were never likely to be finished. We are told that Nausicaa,daughter of king Alcinous, who met Ulysses shipwrecked on her father’s coast, went down to the shore, accompanied by her maidens, to wash clothes; and princess as she was, she carried her dinner with her.

Women grinding corn, after the manner of the Israelites, are alluded to by old Greek authors; and that they were in the habit of spinning with a distaff as they walked, is to be inferred from the fact that it was considered a bad omen to meet a woman working at her spindle.

As luxury increased, the lines of demarkation between different ranks no doubt became more obvious, and laborious occupations were relinquished by the wealthy. It is likewise probable that restraints became less and less rigid. Women, in later times, certainly joined the men in entertainments at Aspasia’s house, and the remains of an ancient picture leads to the conjecture that at some period they attended the theatres. It is recorded that certain women disguised themselves in male attire, and went to Academus to listen to the philosophy of Plato; and when this desire for knowledge began to prevail, it could not be long before it manifested itself in casting off the fetters prescribed by custom. Individuals there were, as there ever will be, of both sexes, who were in advance of the people among whom they lived. Beside the far-famed Sappho and Aspasia, there was Corinna, the Theban poetess, who is said to have five times carried the prize from Pindar; and there was Arete, daughter of Aristippus, who taught philosophy and the sciences to her son: from this circumstance the young man was called Metrodidactos, i. e. Taught-by-his-mother.

Increasing luxury evidently did not produce universal corruption; for the wife of Phocion was a model of prudence, simplicity, and domestic virtue. When one of the actors, who was to represent a queen, demanded a more pompous retinue, Melanthius, who was at the charge of the exhibition, said: “Phocion’s wife appears in public with a single maid-servant; and dost thou come here to show thy pride, and corrupt our women?” The audience received this remark with a thunder of applause. This same modest matron, when a lady exhibited many jewels in her presence, replied: “Phocion is my greatest ornament, who is now called for the twentieth time to command the armies of Athens.” Plutarch, who lived as late as the time of Trajan, bears testimony that his wife Timoxena was far above the frivolity and affectation, which characterized many of her sex; that she cared little for dress or parade; and was chiefly desirous to perform all the duties, and observe all the proprieties of life.

Of the amusements of the Grecian women we know little. Religious festivals no doubt constituted a large portion of their recreations. Many dances were used on these occasions; among which was the Caryatides, a Spartan dance, in honor of Diana. Theseus, who invented a circular dance called the Crane, is said to have been the first who introduced the custom of men and women dancing together. Various musical instruments were in use, such as the harp and the cythara, and women doubtless played upon these, as well as joined in the songs appropriated to various festivals. Female characters at the theatre were performed entirely by men in disguise.

Ladies of rank were at all periods accompanied by attendants; and among them was generally some old nurse, or matron, continually about their persons. Two such are described as waiting upon Penelope, beside a numerous band of maidens, whom she guided in the labors of the distaff and the loom.

The Grecian dress consisted of sandals for the feet, and an ample flowing robe, without sleeves, fastened at the waist by a girdle. The wealthy wore purple, and other rich colors; the common class usually wore white, for the economy of having it dyed when it became soiled. Jewels, expensive embroidery, and delicious perfumes, were used in great profusion by those who could afford them. It is supposed that women stained their eyebrows black, and stained the tips of their fingers rose-color, after the manner of the East. They took great pains to keep their teeth in perfection, and some affirm that they painted their lips with vermillion.

According to Socrates, the most costly female wardrobe in his time might be valued at about fifty minæ, or one hundred and sixty pounds, nine shillings, and two pence.

Until the time of Cecrops, the Grecians lived without the institution of marriage; but his laws on that subject, being found conducive to the public good, soon became generally observed. He expressly forbade polygamy; but at certain periods, when great numbers of men had been slain in battle, temporary laws were passed allowing men to take more than one wife. Euripides is said to have imbibed a dislike to the whole sex by having two wives at once, who made his house a perpetual scene of dissension. It was allowable for a man to marry his sister by the father’s side, but not by the mother’s. Cimon married his sister Elpinice, because his father’s misfortunes had left him too poor to provide a suitable match for her; but afterward, when Callias, a rich Athenian, became in love with Elpinice, and offered to pay all her father’s fines, if she would consent to be his wife, Cimon divorced her, and gave her to him.

Parents negotiated matches for their children; and neither young men nor maidens presumed to marry without the consent of both father and mother.

In Athens, heiresses were compelled by law to marry their nearest kinsmen, in order to preserve the fortune in the family; but if he chanced to be old and superannuated, a younger relative was admitted into the household, and in all respects considered the lady’s husband, except in having a legal claim to her inheritance.

When a female orphan was left without adequate support, the nearest relative was obliged to marry her, or settle a portion upon her according to his wealth and rank. When the connections were numerous, they often combined together to contribute the required sum.

Any foreigner who married an Athenian woman was liable to be sold, together with his estate, and a third part given to the accuser. Any foreign woman, who married a citizen of Athens, was liable to be sold for a slave, and the man was likewise fined a thousand drachmas. These laws fell into disuse; but were revived by Pericles for a short period, during which five thousand Athenian citizens were sold on account of foreign alliances.

It was common for Grecian lovers to deck the doors of their beloved with garlands, and pour libations of wine near the threshold, because this was the manner in which Cupid was worshipped at his temple. They likewise inscribed her name on trees, on the walls of their houses, and on the books they used. These inscriptions were generally accompanied by some flattering epithet. In allusion to this custom, one of the characters in Euripides says he never should have a good opinion of women, though all the pines in mount Ida were filled with their names. When a person’s garland was untied, it was taken as a sign of his being in love; and when women were seen weaving wreaths, they were accused of being love-sick.

Various magical arts and spells were in use to discover the state of each other’s affections. The Thessalian women were famous for their skill in these matters; and the Grecian maidens were in the habit of applying to them for assistance; thus one in Theocritus says:

“To Agrio too I made the same demand,

A cunning woman she, I crossed her hand;

She turned the sieve and shears, and told me true,

That I should love, but not be loved by you.”

Many charms and philtres were likewise in use to procure affection, when their love was unsuccessful. These charms were sometimes compounded with blood of doves, the bones of snakes and toads, screech-owl’s feathers, bands of wool twisted upon a wheel, and if possible from the neck of one who had hanged himself. Sometimes pills, roots, and powerful herbs, were the chosen ingredients; and instances occurred wherein the unfortunate victims of superstition lost their reason by the administration of these dangerous philtres. Images of wax were sometimes made and placed before the fire to melt, while certain spells were pronounced; this was done from the idea that there was some mysterious sympathy between the wax and the heart of the beloved object. Sometimes one who was forsaken and indignant made an image of clay and placed it beside the wax, that while one melted the other might harden; they believed that the heart of the rejected thus became stern and unrelenting, while the faithless lover was softened by affection. Other enchantments, too various to mention, were used by those who wished to effect similar purposes.

Particular regard was paid to lucky seasons and omens for the wedding day. The full of the moon was considered a favorable time, and the conjunction of the sun and moon was peculiarly auspicious. The sixteenth day of the month was regarded as more unlucky than any other. It was supposed that trees planted on that day would wither and die, and that girls who were either born or married at such a date were destined to misery; but for a boy it was considered a lucky augury to be born on the sixteenth.

Before marriage, the Grecian maidens offered baskets of fruit to Diana, and many other ceremonies were performed in her temple. On account of her own aversion to wedlock, it was deemed peculiarly desirable to appease her indignation, and propitiate her favor. Sacrifices were likewise offered to Juno, Minerva, Venus, the Fates, and the Graces. When the victim was opened, the gall was taken out, and thrown behind the altar, as a symbol that all anger and malice must be cast aside. The entrails were carefully examined by soothsayers, and if any unlucky omen presented itself, the contract was dissolved, as displeasing to the gods. The most fortunate omen that could appear was a pair of turtles, because those birds are remarkable for constant affection to each other; if one appeared alone, it was thought to prognosticate separation and sorrow to the young couple.

In many places the bride was required to cut off some of her ringlets and offer them to the gods of marriage, at the same time pouring libations on their altars.

Both bride and bridegroom wore bright colored garments, and were adorned with garlands, composed of flowers sacred to Venus, and other deities supposed to preside over nuptials. The house where the wedding was celebrated was likewise decked with garlands.

The Bœotians used wreaths of wild asparagus, which is full of thorns, but bears excellent fruit; it was therefore thought to resemble ladies, who give their lovers some trouble in gaining their hearts, but whose affection is a sweet reward. The bride carried an earthen vessel full of parched barley, and was accompanied by a maid bearing a sieve, to signify her obligation to attend to domestic concerns; a pestle was likewise tied to the door, for the same purpose. The bride was usually conveyed in a chariot from her father’s house to her husband’s in the evening. She sat in the middle, with the bridegroom on one side, and one of her most intimate female friends on the other. A widower was not allowed to attend his bride, but sent one of his friends for that purpose. Blazing torches were carried before the young couple, and music followed them. Homer thus describes a bridal procession:

“The youthful dancers in a circle bound

To the soft flute, and cittern’s silver sound;

Through the fair streets, the matrons in a row

Stand in their porches, and enjoy the show.”

When the chariot arrived at the bridegroom’s dwelling, the axletree was burnt, to signify that the bride was never to return to the paternal roof. As they entered, figs and various kinds of fruit were poured on their heads, as an indication of future plenty. A sumptuous banquet was prepared for relations and friends, after which the company diverted themselves with dances and hymeneal songs.

At Athens, it was customary for a boy to come in during the feast, covered with thorn boughs and scorns, bearing a basket full of bread, and singing, “I have left the worse and found the better.” Some have supposed this was in commemoration of their change of diet from acorns to corn, but Dr. Potter’s supposition seems much more probable; viz. that it was intended to indicate the superiority of marriage over single life.

In Athens, the bride’s feet were always washed in water brought from the fountain of Callirhoe, which was supposed to possess some peculiar virtue. She was lighted to her apartment with several torches. Around one of these flambeaux, the mother tied the hair-lace of her newly wedded daughter, taken from her head for that purpose. Mothers considered it a great misfortune if illness, or any accident, prevented them from performing this ceremony. The married couple ate a quince together, to remind them that their conversation with each other should be sweet and agreeable. The company remained until late at night, dancing and singing songs filled with praises of the bridegroom and bride, and wishes for their happiness. In the morning they returned, and again saluted them with songs. The solemnities continued several days; during which relations and friends offered gifts, consisting of golden vessels, couches, ointment boxes, combs, sandals, &c., carried in great state to the house of the bridegroom by women, preceded by a boy in white apparel, with a torch in his hand, and another bearing a basket of flowers. It was likewise customary for the bridegroom and his friends to give presents to the bride, on the third day after the wedding, which was the first time she appeared unveiled.

The old Athenian laws ordered that men should be thirty-five and women twenty-six, before they married; but Plato considered thirty a suitable age for the bridegroom, and other writers approved of brides as young as eighteen, or fifteen. Grecian women never changed the name they received when infants: thus Xantippe would be distinguished from another of the same name, by being called Xantippe, the wife of Socrates.

In the primitive ages women were purchased by their husbands, and received no dowry from relations; but with the progress of civilization and wealth this custom disappeared, and wives were respected in proportion to the value of their marriage portion. Medea, in Euripides, complains that women were the most miserable of the human race, because they were obliged to buy their own masters at a dear rate. Those who brought no dowry were liable to be spoken of contemptuously, as if they were slaves rather than lawful wives. Hence, when men married women without fortune, they generally gave a written instrument acknowledging the receipt of a dowry. Those who received munificent portions required a greater degree of respect, and expected additional privileges on that account. Hermione, in Euripides, is enraged that the captive Andromache should pretend to rival her in the affections of Pyrrhus; and she thus addresses her:

“With these resplendent ornaments of gold

Decking my tresses, in this robe arrayed,

Which bright with various tinctured radiance flames,

Not from the house of Peleus or Achilles

A bridal gift, I come. In Sparta this

From Menelaus, my father, I received

With a rich dowry: therefore I may speak

Freely, and thus to you address my words.

Woman! would’st thou, a slave, beneath the spear

A captive, keep possession of this house,

And drive me out?”

Some have supposed that Solon intended to forbid dowries, because one of his laws declares, “A bride shall not carry with her to her husband above three garments, and vessels of small value.” But this was probably intended merely to prevent extravagance in dress and furniture; for he allowed men who had no sons to leave their estates to daughters, and express laws were made to secure the property in the family, by regulating the marriage of heiresses. The daughters of several Grecian monarchs carried their husbands whole kingdoms for a dowry. When distinguished men died in poverty, the state sometimes provided for their children. Thus the Athenians gave three hundred drachmas to each of the orphan daughters of Aristides, and bestowed a farm belonging to the city upon the grand-daughter of their famous patriot, Aristogiton. Phares, of Chalcedon, made a law that rich men should give a portion to their daughters when they married poor men, but receive none with their sons’ wives. As luxury increased, it followed, as an inevitable consequence, that marriages were more and more made with a view to the acquisition of wealth; and fathers were disappointed at the birth of a daughter, on account of the expense attending her establishment. It was customary for the bridegroom to build and furnish the house, and to make a settlement large in proportion to her dowry, for the support of his wife in case of death or divorce; but unless a written receipt of dowry could be produced by the woman’s friends, the husband could not be compelled to allow a separate maintenance. Heirs were bound by law to support the wives of those from whom they received estates.

When sons became of age, they enjoyed their mother’s fortune during her lifetime, affording her a maintenance in proportion to her rank. If a woman died without children, her dowry returned to the relative by whom it had been bestowed.

Girls who had no fathers were disposed of by their brothers; and if they had neither parents nor brethren, the duty devolved upon grandfathers, or guardians. Sometimes husbands betrothed their wives to other persons on their death-beds. The father of Demosthenes gave his wife to one Aphobus, with a considerable portion. Aphobus took the portion, but refused to marry the woman after the death of her husband; in consequence of which her son appealed to the magistrates. The same orator engaged in the defence of Phormio, who having been a faithful slave, his master, before he died, bestowed upon him freedom and his wife.

The forms of betrothing varied in some particulars in different cities, but bore a general resemblance. The parties took each other by the right hand, promised fidelity, and sometimes kissed each other, while the relative of the woman pronounced these, or similar words: “I bestow upon thee, ——, my daughter, or my sister, or my ward, with such and such money, lands, cattle, or flocks, for her dowry.”

In case of divorce, a man was obliged to restore his wife’s portion, and was required to pay monthly interest upon it, so long as he detained it from her.

In general the Grecian laws allowed men to put away their wives upon slight occasions; even the fear of having too large a family was considered sufficient ground for divorce. A woman incurred great scandal in departing from her husband. In Athens, if wives had reason to complain of their husbands, they could appeal to the appointed magistrate, by appearing publicly in court, and placing in his hands a written statement of their grievances. Hipparete, the wife of Alcibiades, losing all patience with his continued profligacy, availed herself of this privilege; but when she presented herself before the archon, Alcibiades seized her by force, and carried her off; no person presuming to interfere with his authority.

It was not unusual for the marriage tie to be dissolved with consent of both parties. Thus Pericles and his wife being weary of each other’s society, he bestowed her upon another man, with her own free will and consent. There is likewise reason to suppose that men sometimes lent their wives to each other, without any of the parties incurring blame by the transaction; but when intrigues were carried on without the husband’s sanction, severe penalties were incurred. Women were sometimes put to death, but more generally sold into slavery. They were never after allowed to enter the temples, or wear any but the most ordinary clothing. Whoever found them disobeying these laws, might tear off their garments, and beat them with any degree of severity that did not endanger their life or limbs.

Wealthy paramours generally brought themselves out of difficulty by paying a heavy fine; but those unable to do this, were liable to very severe and disgraceful punishments.

Although the law allowed but one wife, it was thought no dishonor to keep a train of mistresses, who were usually captives taken in war, or women stolen by Grecian sailors and brought home for sale. The public class of women was composed of individuals derived from similar sources; hence the term “strange woman,” (meaning a foreign woman,) was a term of reproach with the Grecians, as well as the Jews. This shameless class were required by Grecian laws to wear flowered garments, by way of distinction from the modest apparel of virtuous women; and various texts of Scripture lead to the supposition that a similar custom prevailed among the Israelites. Some of them acquired immense wealth; and, what is much more singular, they in some instances enjoyed a degree of influence and consideration unattainable by women of purer manners.

When Thebes was demolished by Alexander, Phryne agreed to rebuild the entire walls at her own expense, if they would engrave on them this inscription: “These walls were destroyed by Alexander, but raised again by Phryne the courtesan.” Phryne had a statue of gold at Delphi, placed between two kings. Theopompus, in his letter to Alexander, speaking of a magnificent mausoleum near Athens, says: “This distinguished mark of public respect a courtesan has received; while not one of all those who perished in Asia, fighting for the general safety of Greece, has been thought worthy to receive a similar honor.” Aspasia, first the mistress and afterward the wife of Pericles, obtained unrivalled influence and distinction. The most celebrated of the Athenian philosophers, orators, and poets, delighted in her society, and statesmen consulted her in political emergencies. They even carried their wives and daughters to her house, that they might there study agreeable manners and graceful deportment. This, together with the fact that Pericles made her his wife, and to the day of his death retained such a strong affection for her, that he never left her to go to the senate without bestowing a parting kiss, seems to imply that she could not have been so shockingly depraved as many writers have supposed. It is more probable that she deserves to rank in the same class as the Gabrielles, and Pompadours of modern times. The public and distinguished attention such women received in Greece, was no doubt owing to the fact that they alone dared to throw off the rigorous restraints imposed upon the sex, and devote themselves to graceful accomplishments, seductive manners, and agreeable learning. For this reason it was generally taken for granted that women of very strong, well-cultivated minds were less scrupulous about modesty, than those who lived in ignorance and seclusion. Sappho, the celebrated poetess, has by no means descended to posterity with an untarnished name. But a degree of injustice is no doubt done to her memory, by understanding the fervent language of the Greeks as similar epithets would be understood in the dialect of colder climes. Had Sappho been the most profligate of woman-kind, she would not have been likely to destroy herself for love of one individual. She was the first woman who jumped from the famous promontory of Leucate, called the Lover’s Leap. The superstition prevailed that those who could perform this feat, and be taken up alive, would be cured of their passion.

Many ceremonies were performed by Grecian women in the temple of Eleutho, who presided over the birth of children. During the hours of illness it was customary to hold palm branches in their hands, and invoke the favor of this goddess. The old laws of Athens expressly forbade that women or slaves should practise physic; but one Agnodice, having disguised herself in male attire, studied the art under a skilful professor, and made the fact known to many of her own sex, who gladly agreed to employ her in preference to all others. The jealousy of the physicians led to a discovery of the plot, and Agnodice would have been ruined, had not all the principal matrons of Athens appeared in court and pleaded strongly in her favor. In consequence of their entreaties, the old law was repealed, and women were allowed the attendance of female physicians.

The Grecians generally wrapped infants in swaddling bands, lest their tender limbs should become distorted. In Athens newly born babes were covered with a cloth on which a gorgon’s head was embroidered, because that was represented on the shield of Minerva, to whose care the child was consigned. It was likewise customary to lay boys upon bucklers, as a prognostic of future valor. Infants were often placed upon other things bearing some resemblance to the sort of life for which they were designed. It was common to put them in vans made to winnow corn, and therefore considered as emblems of agricultural plenty. Sometimes instead of a real van, an image of it was made of gold or silver. Wealthy Athenians universally laid young infants upon dragons of gold, in memory of one of their kings, who, when an unprotected babe, was said to have been watched by dragons. When a child was five days old, the nurse took it in her arms and ran round the hearth, thus putting it under the protection of the household gods, to whom the hearth served as an altar. This festival was celebrated with great joy. Friends brought in their gifts, and partook of a feast, peculiar to the occasion. If the child was a boy, the door was decorated with an olive garland; if a girl, wool was a substitute for the olive, in token of the spinning and weaving destined to occupy her maturer years. On the tenth day, another entertainment was given, and the child received its name, which was usually bestowed by the father. It was common to choose the name of some illustrious or beloved ancestor; but names describing personal and moral qualities were frequently given, such as the ruddy faced, the eagle-nosed, the ox-eyed, the gifted, the lover of his brethren, &c.

When the child was forty days old, another festival was kept, and the mother offered sacrifices in Diana’s temple. Athenian nurses quieted fretful babes with sponges dipped in honey.

It was common to expose children, especially females, on account of the expense attending their settlement. Posidippus says:

‘A man, though poor, will not expose his son,

But if he’s rich, will scarce preserve his daughter.’

The children thus exposed were wrapped in swaddling bands, and placed in a sort of ark, or basket. Sometimes jewels were attached to them, as a means of discovery, if any person should find and nourish them; or, as some have supposed, from the superstition that it was important for the child to die with some of the parents’ property in its possession.

The Thebans disliked this cruel practice, and their laws made it a capital offence. Those who were too poor to rear their children, were ordered to carry them to the magistrates, who nourished them, and afterwards received their services in payment.

The Grecians believed in the power of the evil eye, especially over little children. It was generally attributed to one under the influence of malice or envy; and they endeavored to protect an infant from its baneful effects, by tying threads of various colors round the neck, and touching its forehead and lips with spittle mixed with earth.

Filial respect and affection, the distinguishing virtue of olden times, was in high repute among the Grecians. The story of the daughter who nourished her imprisoned father with her own milk, is too well known to need repetition. Alexander the Great having received a letter from Antipater full of charges against Olympias, for her interference with public affairs, the monarch read it, and said, “Antipater knows not that one tear from a mother can blot out a thousand such complaints.”

Solon made a law that women should not join in the public funeral solemnities even of their nearest relations, unless they were threescore years old; but this law did not continue to be observed; for gallants are described as falling in love with young women whom they saw at funerals. It is supposed that men and women formed separate portions of the procession; the former preceding the corpse, the latter following it. Mourning women were employed to sing dirges, and bewail the dead. They beat their breasts, disfigured their faces, and made use of other violent demonstrations of grief. The female relatives of the departed often joined in these excesses, altogether regardless of the hideous scars produced thereby; but this practice was forbidden by Solon. In many places it was the custom for women to shave their heads, and spread their tresses over the corpse. They laid aside all ornaments and rich attire, and wore black garments made of coarse materials. Those who were joined by near relationship, or strong affection, generally shared the same funeral urn. Thus Halcyone, whose husband perished at sea, says:

“Though in one urn our ashes be not laid,

On the same marble shall our names be read;

In amorous folds the circling words shall join,

And show how much I loved—how you was only mine.”

A very beautiful bas-relief found at Athens, represents a woman seated, while a man with three little children seem bidding her an affectionate farewell. It probably marked the sleeping-place of some beloved wife and mother. At the funeral of a married woman, matrons carried vases of water to pour upon her grave; girls performed this office for maidens, and boys for young men. These processions of water-bearers are often represented on ancient sepulchres. An owl, a muzzle, and a pair of reins, were often carved on the tombs of women; as emblems of watchfulness, silence, and careful superintendence of the family.

It was not uncommon for widows to marry a second time; but those who did otherwise were regarded with peculiar respect. Charondas excluded from public councils those men who married a second wife, when they already had children. “Those who do not consult the good of their own family cannot advise well for the good of the country,” said he. “He whose first marriage has been happy, ought to rest satisfied with his share of good fortune; if unhappy, he is out of his senses to incur another risk.”

In very early times the priestesses were allowed to marry; thus Homer speaks of the beautiful Theano, wife of Antenor, who was unanimously chosen priestess of Minerva. At later periods, all who were devoted to the service of the temples were required to live unmarried.

The oracles of the gods were universally uttered by women. The most celebrated was the Delphian oracle of Apollo. The priestess who uttered the prophetic words was called Pythia, or Pythonissa. She was obliged to observe the strictest rules of temperance and virtue, and to clothe herself in simple, modest, and maidenly apparel. They neither anointed nor wore purple garments, because such habits belonged to the rich and luxurious. In early times the Pythia was chosen from young maidens; but in consequence of a brutal insult offered to one of them, the selection was ever after made from women more than fifty years old. Before the prophetess ascended the tripus, where she was to receive inspiration, she bathed herself, especially her hair, in the fountain of Castalia, at the foot of Parnassus. When she seated herself upon the tripus, she shook the laurel tree, that grew near it, and sometimes ate the leaves, which were thought to contain some virtue favorable to prophecy. In a short time she began to foam at the mouth, tear her hair, and cut her flesh, like a maniac. The words she uttered during these paroxysms were the oracles. The fits were more or less violent; sometimes comparatively gentle. Plutarch speaks of one enraged to such a degree that the terrified priests ran from her, and she died soon after. The time of consulting the oracle was only one month, in the spring of the year.

Women had their share in sacred festivals among the Greeks. In the processions of the Panathenæa, in honor of Minerva, women clothed in white carried torches and the sacred baskets. At the annual solemnity in honor of Hyacinthus and Apollo, the Laconian women appeared in magnificent covered chariots, and sometimes in open race-chariots. At the processions in honor of Juno, her priestess, who was always a matron of the highest rank, rode in a chariot drawn by white oxen. Aristophanes describes the wife and daughter of a citizen as assisting in the ceremonials of a rural sacrifice to Bacchus. The girl carried a golden basket filled with fruit, and a ladle with which certain herbs were poured over the sacred cakes. Her father followed, singing a hymn to the god, while the mother, standing on the house-top, watched the procession, and charged her daughter to conduct herself like a lady, as she was, and to be cautious lest her golden ornaments were stolen in the crowd.

One of the most ancient ceremonies among the Greek women was that of bewailing annually, with dirges and loud cries, the death of Adonis. Processions were formed, and images of Venus and Adonis carried aloft, together with shells filled with earth, in which lettuces were growing. This was done in commemoration of Adonis laid out by Venus on a bed of lettuce.

In Attica, all girls not over ten or under five were consecrated to the service of Diana, during a solemnity which took place once in five years. On that occasion all female children of the proper age appeared dressed in yellow robes, while victims were offered to the goddess, and certain men sung one of Homer’s Iliads. No Athenian woman was allowed to be married unless this ceremony had been performed.

The festival in honor of Ceres was observed with much solemnity at Athens. None but free-born women were allowed to be present; and every husband who received a portion of three talents with his wife, was obliged to assist in defraying the expenses. The women were assisted in the ceremonials by a priest, who wore a crown, and by certain maidens, who were strictly secluded, kept under severe discipline, and maintained at the public charge. The solemnity lasted four days. All the women who aided in it were clothed in simple white garments, without ornaments or flowers. Not the slightest immodesty or merriment was permitted; but it was a custom to say jesting things to each other, in memory of Jambe, who by a jest extorted a smile from Ceres, when she was discouraged and melancholy. On one of the festival days, the women walked in procession to Eleusis, carrying books on their heads, in memory of Ceres, who was said to have first taught mankind the use of laws; on this occasion it was against the law for any one to ride in a chariot. There was likewise a mysterious sacrifice to Ceres, from which all men were excluded; this was said to have been because in a dangerous war, the prayers of women so prevailed with the gods, that their enemies were driven away.

The custom of offering human beings as sacrifices to the gods was regarded with great abhorrence by the primitive Greeks; but several instances occurred in later times where captives taken in war were devoted to this purpose. There is reason to suppose that the victims were generally men; but there were exceptions to this remark. Bacchus had an altar in Arcadia, upon which young damsels were beaten to death with bundles of rods. Iphigenia, daughter of Agamemnon, was likewise about to be sacrificed to Diana, because the soothsayer so decreed, when the Greeks were kept back from the Trojan war by contrary winds; and Macaria, the daughter of Hercules and Dejanira, voluntarily offered herself as a victim, when the oracle declared that one of her father’s family must die, to insure victory over their enemies. Great honors were paid to the memory of this patriotic girl, and a fountain in Marathon was called by her name.

The Athenian slaves were much protected by the laws. If a female slave had cause to complain of any want of respect to the laws of modesty, she could seek the protection of the temple, and demand a change of owners; and such appeals were never discountenanced or neglected by the magistrates.

The Milesian women being at one period much addicted to suicide, a law was passed that all who died by their own hands should be exposed to the public; and this effectually prevented an evil, which no other means had been able to prevent.

The customs of Sparta differed in many respects from the rest of Greece. When a match was decided upon, the mother, or nurse of the bride, or some other woman who presided over the arrangements, shaved the girl’s hair, dressed her in masculine attire, and left her alone in an apartment at evening. The lover, in his every-day clothes, sought an opportunity to enter by stealth, but took care to return to his own abode before daylight, that his absence might not be detected by his companions. In this manner only did custom allow them to visit their wives, until they became mothers. Lycurgus passed a law forbidding any dowry to be given to daughters, in order that marriage might take place from motives of affection only. Marriage was much encouraged in every part of Greece, and peculiarly so in Sparta. The age at which both sexes might marry was prescribed by law, and any man who lived without a wife beyond the limited time was liable to severe penalties. Once every winter, they were compelled to run round the forum without clothing, and sing a certain song, the words of which exposed them to ridicule; they were not allowed to be present at the exercises where beautiful young maidens contended; on a certain festival, the women were allowed to drag them round an altar, beating them with their fists; and young people were not required to treat them with the same degree of respect that belonged to fathers of families.

Polygamy was not allowed, and divorces were extremely rare; but the laws encouraged husbands to lend their wives when they thought proper. Lycurgus reversed the Athenian custom, and allowed brother and sister of the same mother to marry, while he forbade it if they both had the same father. In Sparta there was a very ancient statue, called Venus Juno, to which mothers offered sacrifice on the occasion of a daughter’s marriage.

Damsels appeared abroad unveiled, but married women covered their faces. Charilus, being asked the reason of this practice, replied, “Girls wish to obtain husbands, and wives aim only at keeping those they already have.” Lycurgus ordered that maidens should exercise themselves with running, wrestling, throwing quoits, and casting darts, with the view of making them healthy and vigorous; and for fear they might have too much fastidiousness and refinement, he ordered them to appear on these occasions without clothing. All the magistrates and young men assembled to witness their performances, a part of which were composed of dances and songs. These songs consisted of eulogiums upon such men as had distinguished themselves by bravery, and satirical allusions to those who had been cowardly or effeminate; and as they were sung in hearing of the senate and people, no inconsiderable degree of pride or shame was excited in those who were the subjects of them.

The Spartans bathed new-born infants in wine, from the idea that vigorous children would be strengthened by it, while those who were weakly would either faint, or fall into convulsions. Fathers were not allowed to educate and nourish their own children, if they were desirous to do so. All infants, being considered the property of the commonwealth, were brought to the magistrates to be examined. If vigorous and well formed, a certain portion of land was allotted for their maintenance; but if they appeared sickly or deformed, they were thrown into a deep cavern and left to perish.

The Spartan nurses were so celebrated, that they were eagerly sought for by people of other countries. They never used swaddling bands, and religiously observed the ceremony of laying infants upon bucklers, as soon as they were born. They taught children to eat any kind of food, or to endure the privation of it for a long time; not to be afraid when left alone, or in the dark; to be ashamed of crying, and proud to take care of themselves.

The Spartans mourned for deceased relations with great composure and moderation; though when a king died, it was customary for men, women, and slaves, to meet together in great numbers, and tear the flesh from their foreheads with sharp instruments. Indeed, in all things they endeavored to make their own interest and feelings subordinate to the public good. When news came of the disastrous overthrow of the Lacedæmonian army at Leuctra, those matrons who expected to receive their sons alive from the battle, were silent and melancholy; while those who received an account that their children were slain in battle, went to the temples to offer thanksgivings, and congratulated each other with every demonstration of joy.

The Lacedæmonians usually carried bodies to the grave on bucklers; hence the command of the Spartan mother to her son, “either to bring his buckler back from the wars, or be brought upon it.”

Some foreign women said to Gorgo, wife of king Leonidas, “You Spartans are the only women that govern men.” “Because we are the only women who give birth to men,” she replied. This answer was in allusion to their own strength and vigor, and to the pains they took to make their boys bold and hardy.

The Lacedæmonian women seem to have had a share in all the concerns of the commonwealth; and during the early portions of their history they appear to have been well worthy of the respect paid to them. When a new senator was chosen, he was crowned with a garland, and the women assembled to sing his domestic virtues and his warlike courage. At the public feast given in honor of his election, he called the female relative for whom he had the greatest esteem and gave her a portion, saying, “That which I received as a mark of honor, I give to you.” When Cleomenes, king of Sparta, was beset with powerful enemies, the king of Egypt agreed to furnish him with succors, provided he would send his mother and his children as hostages. Filial respect and tenderness made the prince extremely unwilling to name this requisition. His mother, perceiving that he made an effort to conceal something from her, persuaded her friends to tell her what it was. As soon as she heard it, she laughed outright, and said, “Was this the thing you so long hesitated to communicate? Put us on board a ship, and send this old carcase of mine wherever you think it may be of the most use to Sparta, before age renders it good for nothing, and sinks it into the grave.” When everything was ready for departure, she, being alone with her son, saw that he struggled hard with emotion. She threw her arms around him, and said, “King of the Lacedæmonians, be careful that we do nothing unworthy of Sparta! This alone is in our power; the event belongs to the gods.”

When Cleombrotus rebelled against his wife’s father, in spite of her entreaties, and usurped the kingdom, Chelonis left her husband and followed the fallen fortunes of her parent; but when the tide turned, and Cleombrotus was in disgrace and danger, she joined her husband as a suppliant for royal mercy, and was found sitting by him, with the utmost tenderness, with her two children at her feet. She assured her father that if his submission and her tears could not save his life, she would die before him. The king, softened by her entreaties, changed the intended sentence of death into exile, and begged his daughter to remain with a father who loved her so affectionately. But Chelonis could not be persuaded. She followed her husband into banishment.

Such was the character of Spartan women in the earlier periods of their history; but in later times their boldness and immodesty increased to such a degree that they became a by-word and a reproach throughout Greece.

In Grecian mythology, the goddesses are about as numerous and important as the gods. That Beauty, Health, and Majesty should be represented as female deities, is by no means remarkable; but, considering the estimation in which women were held, it is somewhat singular that Wisdom should have been a goddess, and that sister muses should have presided over history, epic poetry, dramatic poetry, and astronomy. The tradition that Ceres first taught the use of laws does not probably imply that legislation was invented by a woman; but that as men left a wandering life, and devoted themselves to agriculture, (of which Ceres was the personification,) they began to perceive the necessity of laws for mutual defence and protection.

In the earliest and best days of Rome, the first magistrates and generals of armies ploughed their own fields, and threshed their own grain. Integrity, industry, and simplicity, were the prevailing virtues of the times; and the character of women was, as it always must be, in accordance with that of men. Columella says: “Roman husbands, having completed the labors of the day, entered their houses, free from all care, and there enjoyed perfect repose. There reigned union, and concord, and industry, supported by mutual affection. The most beautiful woman depended for distinction only on her economy, and endeavors to assist in crowning her husband’s diligence with prosperity. All was in common between them; nothing was thought to belong more to one than another. The wife, by her assiduity and activity within doors, equalled and seconded the industry and labor of her husband.”

It was common for sons to marry and bring home their wives to the paternal estate. Plutarch says: “There were not fewer than sixteen of the Ælian family and name, who had only a small house and one farm among them; and in this house they all lived, with their wives and many children. Here dwelt the daughter of Æmilius, who had been twice consul, and had triumphed twice; not ashamed of her husband’s poverty, but admiring that virtue which kept him poor.”

Tanaquil, wife of Tarquin the First, one of the best kings of Rome, was noted for her industry and ingenuity, as well as energy and ambition. Her distaff was hung up in the temple of Hercules, and her girdle, with a robe she embroidered for her son-in-law, were long preserved with the utmost veneration. Her political influence seems to have been great, and her liberality munificent. Her husband was originally a private citizen of Tarquinia; but her knowledge of augury led her to predict that an uncommon destiny awaited him at Rome, and she persuaded him to go thither. After his death, she succeeded in raising her son-in-law, Servius Tullius, to the throne.

Lucretia, a young matron of high rank, was found busy among her maidens, assisting their spinning and weaving, and preparation of wool, when her husband arrived with his guests, late in the evening. The high value placed upon a stainless reputation may be inferred from the fact that Lucretia would not survive dishonor, though she had been the blameless victim of another’s vices.

Cornelia, the daughter of Scipio Africanus, was courted by a monarch, but preferred being the wife of Sempronius Gracchus, a Roman citizen. After the death of her husband, she took the entire management of his estate, and the education of her sons. She was distinguished for virtue, learning, and good sense. She wrote and spoke with uncommon elegance and purity. Cicero and Quintilian bestow high praise upon her letters. The eloquence of her children was attributed to her careful superintendence. When a Campanian lady ostentatiously displayed a profusion of jewels, and begged Cornelia to show hers, she exhibited her boys, just returned from school, saying: “These are my jewels; the only ornaments of which I can boast.” During her lifetime, a statue was erected in honor of her character, bearing this inscription: “Cornelia, mother of the Gracchi.”

The rigid decorum of Roman manners may be inferred from the circumstance that Cato expelled a senator, merely because he kissed his wife in the presence of his daughter. “For my own part,” said he, “my wife never embraces me except when it thunders terribly;” adding, by way of joke, “I am a very happy man when Jove is pleased to thunder.”

The superior condition of Roman women, in comparison with the Greeks, may in a great measure be attributed to an event that occurred in the very beginning of their history.

Romulus, being unable to obtain wives for the citizens of his new commonwealth, celebrated public games, to which people of neighboring nations were invited. In the midst of the entertainment he and his soldiers seized a large number of women, principally Sabines, and carried them off to his camp. Their restitution was demanded and refused; but the warlike husbands, anxious to conciliate the affections of wives obtained in a manner so violent, treated them with such tenderness, that the women were themselves unwilling to return to their relatives. This led to a war with the Sabines, and Romulus was closely besieged in his citadel. At this crisis, Hersilia, his wife, asked and obtained an audience with the senate, in which she told them that the women had formed a design of acting as mediators between their husbands and fathers. A decree was immediately passed in favor of the proposition. Every woman was required to leave one of her children, as a hostage of her return; the others they carried in their arms, to soften the feelings of their parents. They proceeded to the Sabine camp, dressed in deep mourning, and knelt at the feet of their relatives. Hersilia described the kindness of their husbands, and their own reluctance to be torn from their families, in a manner so eloquent and pathetic, that an honorable and friendly alliance was soon agreed upon.

In consideration of this important service, the Romans conferred peculiar privileges on women. In capital cases, they were exempted from the jurisdiction of ordinary judges; no immodest language or behavior was allowed in their presence; every one was ordered to give way to them in the street; and a festival was instituted in their honor, called Matronalia, during which they served their slaves at table, and received presents from their husbands.

Three kinds of marriage were in use among the Romans, called confarreatio, coemptio, and usus. The first was established by Romulus, and was the most solemn, as well as the most ancient. A priest, in the presence of at least ten witnesses, pronounced certain words, and sacrificed to the gods a cake made of salt, water, and wheat-flour. The bride and bridegroom ate of this cake, to signify the union which ought to bind them. This manner of celebrating marriage made a wife the partner of all her husband’s substance, and gave her a right to share in the peculiar sacred rites attached to his family. If he died intestate, and without children, she inherited his whole fortune, as a daughter; if he left children, she shared equally with them. If she committed any fault, the husband judged of it in presence of her relations, and punished her at pleasure. Sometimes when women were publicly condemned by law, the penalty was left to the judgment of her husband and relations. The priests of Jupiter were chosen from sons born of this kind of marriage, and the vestal virgins were selected from the daughters.

The coemptio, or mutual purchase, consisted of the bride and bridegroom’s giving each other pieces of money. The man asked the woman, “Are you willing to be the mistress of my family?” She answered, “I am willing;” and then asked him a similar question, to which he replied in the same manner. According to some authors it was accompanied with the same ceremonies, and conferred the same privileges, as the other form of marriage; and it continued in use a long time after confarreatio was out of date.

That which was called usus, or usage, was when a woman, with consent of her parents or guardians, lived a whole year with a man, without being absent from his house three nights. She thus became his wife, and is supposed to have had the same rights and privileges as other wives; but if absent three nights, she was said to have annulled the contract.

No young man was allowed to marry before he was fourteen, and no girl before she was twelve. A man sixty years old was not permitted to marry a woman younger than fifty; and if he was more than sixty, he could not marry a woman of fifty.

Brothers and sisters, uncles and aunts, and cousin-germans, were not permitted to marry each other. For some time it was contrary to law for a patrician to marry a plebeian; but this continued only about five years.

All alliances with women of blemished reputation, or low extraction, were considered dishonorable. No marriage of a Roman with a foreigner could be legal, unless express permission had been first obtained from the government. Cicero even reproached Anthony for marrying Fulvia, because her father was a freed-man. A law was, however, passed, by which only senators, their sons, and grandsons, were forbidden to marry a freed-woman, an actress, or the daughter of an actor. Finally the right of citizenship was granted to all inhabitants of countries belonging to the Roman empire, and the stigma attached to foreign alliances was removed.

Neither sons nor daughters could marry without their father’s approbation. The mother’s consent was usually asked as a matter of propriety, though there was no legal restriction to that effect.

When the consent of parents had been obtained, the relatives held a meeting to settle the articles of contract, which were written and sealed, in presence of witnesses. They broke a straw, according to their custom in making bargains; hence it was called stipulation, from stipula, a straw. This occasion was usually celebrated by a feast, during which the bridegroom made presents to the bride, and gave her a ring, that in early times was plain, and made of iron, but afterwards of gold. It was worn on the fourth finger of the left hand, on account of the idea that a vein went from that finger to the heart. Some of these bridal rings were made of brass or copper, with the figure of a key, to signify that the husband delivered her the keys of his house. Some of them have been found bearing devices; such as I love you. I wish you a happy life. Love me. If, after the espousals, either party wished to retract, they could do so, by observing certain forms.

The marriage portion varied according to the wealth and rank of the parties. It was delivered in money, or secured upon lands; and was paid at three terms fixed by law. The husband was not permitted to alienate it; and in case of divorce, except it took place by his wife’s fault, her relations could reclaim it. If any citizen caused a woman to lose her fair fame, he was obliged to marry her without a portion, or give her one proportioned to her rank. In the first days of the republic, dowries were very small. The senate gave the daughter of Scipio about £35 10s.; and one Megullia was surnamed Dotata, or the Great Fortune, because she had £161 7s. 6d. sterling. But as wealth increased, the marriage portions became greater, until eight or nine thousand pounds sterling was the usual dowry of women of high rank. Seneca says, “The sum that the senate thought sufficient dowry for the daughter of Scipio, would not now suffice even the daughters of our freed-men to buy a mirror.”

No marriage took place without first consulting the auspices, and sacrificing to the gods, especially to Juno, who presided over matrimonial engagements. Like the Greeks, they took the gall from the victims, and threw it behind the altar.

Certain days and festivals were regarded as unlucky for a wedding; particularly those marked in the calendar with black; but widows might marry on those days. The whole month of May was regarded as unfortunate for marriage, and the middle of June peculiarly auspicious. The ceremony was performed at the house of the bride’s father, or nearest relation. She was dressed in a long white robe bordered with purple, and fastened with a girdle made of wool. Her hair was divided into six locks with the point of a spear, and crowned with a wreath of vervain gathered by herself. Her face was covered with a flame-colored veil, and she wore high shoes of the same color. In the evening, she was conducted to her husband’s house. She was taken apparently by force from the arms of her mother, or nearest female relative, in memory of the Sabine women seized by Roman soldiers. Three boys, who had parents living, attended upon her; one supporting each arm, and the third walking before her with a lighted flambeau. Relations and friends eagerly sought to carry away this torch, when they came near the bridegroom’s house; partly on account of some peculiar virtue it was supposed to possess, and partly for fear it should be made use of for some fascination, that would shorten the lives of the young couple.

A young slave followed the bride, carrying, in a covered vase, her toilet, and corals, and children’s playthings of all kinds, accompanied by maidens, bearing distaff, spindle, and wool. A great train of relations and friends attended the nuptial procession. The door of the bridegroom’s house was adorned with festoons, garlands of flowers, and lists of woollen, rubbed with oil, and the fat of swine or wolves, to avert enchantments. When the bride arrived thither, being asked who she was, she answered, “Caia.” This custom was taken from the name of Caia Cœcilia, generally called Tanaquil; and the bride’s answer implied that she intended to imitate such a good and industrious wife. She then bound the door-posts of her bridegroom with woollen fillets, likewise anointed with oil, and the fat of swine or wolves; from this circumstance the Latin word for wife is uxor, which signifies the anointer; and our word uxorious is thence derived.

The bride was gently lifted over her husband’s threshold; for it was reckoned a bad omen to touch it with her feet, because the threshold was sacred to Vesta, who presided over female purity.

As soon as she entered, they sprinkled her with water, and delivered the keys of the house, to show that she was intrusted with the management of the family; and a sheep-skin was spread before her, indicating that she was to work in wool. Both she and her husband were required to touch fire and water; and with the water their feet were afterward bathed. In the early ages they put a yoke about the neck of the young couple, as an emblem of the mutual assistance they were expected to render each other in the cares and duties of life. The Latin word conjugium, a yoke, is the origin of our word conjugial. The bridegroom feasted the relations, friends, and attendants of himself and bride. He was placed at the head of the table, and the bride was laid in his bosom. The feast was distinguished for the abundance, variety, and delicacy of the refreshments. It was accompanied with music. The guests sung to the honor of the newly married an epithalamium, beginning and ending with acclamations, in which was often repeated the name of Thalassius. The following circumstance is supposed to have been the origin of this custom: when the Sabine women were forcibly carried to the Roman camp, one of them, very remarkable for her youthful beauty, attracted so much attention, that quarrels were likely to ensue concerning her. The men who carried her, wishing to avoid any such contention, thought of exclaiming aloud that they were carrying her to Thalassius, a handsome and brave young man, exceedingly beloved by the people. As soon as this was proclaimed, the soldiers withdrew all opposition, and rent the air with acclamations of the hero’s name. The marriage thus prepared for Thalassius proved so happy and prosperous, that the Romans ever after, in their epithalamia, were accustomed to wish the newly-married pair a destiny like his.

The bride was conducted to her apartment by matrons, who had been married to only one husband. The bridegroom scattered nuts among the boys, and the bride consecrated her dolls and playthings to Venus, thereby intimating that they relinquished the sports of childhood. When the guests departed, small presents were distributed among them.

Next day another entertainment was given, when presents were sent to the bride by relations and friends, and she performed certain sacred rites appropriate to the mistress of a family. The goods which a woman brought her husband beside her dowry were called bona paraphernalia.

Daughters generally received the name of their father, or some relation, varied only by ending according to the feminine instead of the masculine gender: thus Hortensia was the daughter of Hortensius; and the two daughters of Mark Antony were named Antonia Major, and Antonia Minor. By way of endearment they frequently made use of those diminutives, to which the language of Italy owes so much of its gracefulness; thus the beloved daughter of Tullius Cicero was called Tulliola. In a numerous family, girls were often distinguished from each other by the diminutives of numbers; as Secundilla, and Quartilla, the Second and the Fourth. At marriage, a woman retained her original name with the addition of her husband’s; thus Cornelia, the wife of Sempronius Gracchus, was called Cornelia Sempronia.

The birth of children was celebrated by a domestic festival, during which the gates were adorned with branches, garlands, and lamps, and a piece of money was deposited in the temple of Juno Lucina, whose office corresponded to the Eleutho of the Grecians. Boys received the family name on the ninth day after birth, and girls on the eighth; but they did not give the prænomen, or, as we should say, the baptismal name, until they took the virile robe, which marked their entrance into manhood; and girls did not receive it till they were married.

Romulus introduced the Spartan custom of exposing all sickly and deformed children; with this restriction, that every child should be nourished three years, in order to try whether it would not, in that interval, attain health and vigor. In later times, this prohibition was disregarded, and the custom of exposing infants became very common.

While the Romans retained their primitive simplicity, mothers nursed their own babes, and would have considered it a great misfortune or reproach, to have employed another to fulfil that tender office; but as luxury increased, indolence and love of pleasure so far conquered maternal affection, that women of rank almost universally consigned their children to the care of female slaves.

Education kept pace with the changing character of the people. At first, children were brought up in habits of laborious industry. When the arts and sciences were introduced, the cultivation of the mind and manners received a considerable degree of attention; and we know that girls shared in these privileges, because when Claudius wished to seize the beautiful Virginia as a slave, in order to deliver her to the infamous Appius, he arrested her as she returned from school, attended by her governante. In the last days of Rome, personal habits were exceedingly luxurious, and education became showy and superficial, because it was acquired from vanity, rather than a love of knowledge. The power of Roman fathers was excessive. They could imprison their children, load them with fetters, make them work with the slaves, sell them, and even put them to death; but mothers had no legal share in this authority. A story is told of a Roman girl, who was starved to death by her father, because she picked the lock of a wine chest, to get at the wine.

The habit of adopting children, even when the parents on both sides were living, was very common. The adopted were subject to the same authority, and received the same share of inheritance, as real sons and daughters. They generally retained the name of their own family, in addition to the one into which they were adopted.

Though the Romans rivalled all preceding nations in justice and kindness toward women, yet husbands were intrusted with a degree of power, which modern nations would consider dangerous. A man might divorce his wife, if she violated the matrimonial vow, poisoned his offspring, brought upon him suppositious children, counterfeited his private keys, or drank wine without his knowledge. Valerius Maximus says that Egnatius Metellus, having detected his wife drinking wine out of a cask, put her to death, and was acquitted by Romulus.

The ancient Romans did not allow women to inherit property; but as wealth increased, fathers did not like to leave their fortunes to distant male relatives, while their daughters were left portionless; they therefore managed to elude the law, by making such provision for their children, as rendered the estates so taken of little value. The people, vexed at these proceedings, passed the Voconian law, by which no woman could inherit an estate, even if she were an only child; but after a time, the right of succession, both in moveables and land, was granted to females after the death of their brothers.

Women could not dispose of property, or transact any business of importance, without the concurrence of a parent, husband, or guardian. Sometimes a man appointed a guardian to his widow, or daughters, and sometimes they were allowed to choose for themselves. In some cases, discreet elderly women were appointed guardians. No women, except the vestal virgins, were allowed to give evidence in a court of justice concerning wills. The favorite attendants of noble Romans were sometimes intrusted with an extraordinary degree of power over the wives of their masters. Justinian’s principal eunuch threatened to chastise the empress, if she did not obey his orders. These facts show that Roman women were by no means admitted to the social equality, which characterizes the intercourse of the sexes at the present time; but they ate and drank with the men, were present at convivial entertainments, enjoyed the evening air in the public groves, accompanied by fathers, husbands, or brothers, and enjoyed many privileges to which the women of neighboring nations were entire strangers.

The Romans treated female captives with shameless brutality. Queens and princesses were compelled to submit to the grossest personal indignities, and were often dragged through the streets chained to the conqueror’s chariot wheels. The stern ferocity that mingled with their better qualities is shown in the story of one of the Horatii, who killed his sister, merely because she wept for her lover slain by his hand; and the example of Marcia, wife of Regulus, who shut up some Carthagenian prisoners in a barrel filled with sharp nails, to revenge her husband, who had been put to death in Carthage. It is, however, true that these actions were not sanctioned by public opinion; for Horatius was punished, and the senate interfered to check the wanton cruelty of Marcia.

The Romans followed the common practice of hiring mourning women to sing funeral songs in praise of the dead. The nearest female relations sometimes tore their garments, and covered their hair with dust. In the funeral procession, sons veiled their faces, and daughters went with uncovered heads and dishevelled hair, contrary to the usual practice of both. They followed the Grecian custom of burning the corpse, and depositing the ashes in an urn. Infants, that died before they had teeth, were buried, not burned; and all children not weaned were carried to the grave by their mothers. The sepulchres were covered with flowers and garlands, and a small altar was placed near, on which libations were made, and incense burnt.

It was thought dishonorable for men to mourn; but the law prescribed that women should mourn ten months for a parent, or a husband. During this time they laid aside ornaments, and purple garments, and staid at home, avoiding all amusements; some even refrained from kindling a fire in the house on account of its cheerful appearance. Under the republic, women dressed in black like the men; but under the emperors, when party-colored garments came in fashion, they wore white for mourning. If a widow married within ten months after her husband’s decease, she was held infamous. Indeed second marriages were never esteemed honorable in women. Even in the most corrupt days of the empire, those who had been married but to one husband were treated with peculiar deference; hence Univira is often found on ancient sepulchres, as an epithet of honor.

Plutarch says maidens never married on festivals, nor widows on working-days, because marriage was honorable to the one and seemed not to be so to the other; for which reason they celebrated the marriage of widows in presence of a few, and on days that called off the attention of the people to other spectacles. Those who remained widows had the first place in certain solemn ceremonies. The crown of chastity was decreed to them; and if they married again, they were never after allowed to enter the temple of that divinity.

The Romans borrowed their mythology from the Grecian, where female deities abound. When they invoked the gods by name, in their temples, the Romans, in order to avoid mistakes, were accustomed to add, “Whether thou art a god, or whether thou art a goddess.” Women, as well as men, filled the sacred office of the priesthood. The vestal virgins were young girls, six in number, devoted to the service of Vesta. When any vacancy occurred, twenty maidens, not younger than six, or older than sixteen, were selected from the families of Roman citizens. It was required that their parents should both be living, and free-born, and that they themselves should be without any bodily imperfection or infirmity. It was determined by lot which of the twenty should be chosen; unless some one, with requisite qualifications, was voluntarily offered by parents, and approved by the pontifex maximus, or high priest. The vestals were bound to their ministry for thirty years. For the first ten, they learned the sacred rites; for the next ten, they performed them; and for the last ten, they taught the younger virgins. It was the business of the vestals to keep the sacred fire continually burning; they watched it in the night time alternately; and whoever allowed it to go out, was severely scourged. The fire was relighted from the rays of the sun, and extraordinary sacrifices were made to avert the unlucky omen. Certain sacred images, on the preservation of which the safety of Rome was supposed to depend, were likewise intrusted to the care of the vestals. Wills and testaments were often deposited in their hands, by people who were afraid that relations would commit frauds and forgeries. They were chosen as the umpires of difficulties between persons of rank; and their prayers were thought to have peculiar influence[Pg 53] with the gods. Even the prætors and consuls, when they met them in the street, lowered their fasces, and went out of the way, to show them respect. They were supported by a public salary; had a lictor to attend them in the streets; rode in chariots; and sat in a distinguished place at the spectacles. Any insult to them was punished with death; and if a criminal chanced to meet one of them on his way to execution, he was immediately set at liberty, provided the vestal affirmed that the meeting was unintentional. They were allowed to make their wills, although under age; and were not subject to the power of parents or guardians, like other women. They were not forced to swear, unless so inclined; and their testimony was admitted concerning wills, though no other female was allowed to give evidence on the subject. Beside these exclusive honors, they enjoyed all the privileges of matrons who had three children.

If any vestal violated her vow of chastity, she was buried alive, with funeral solemnities, after being tried and sentenced; and her paramour was scourged to death in the forum. Such an event was always thought to forebode some dreadful calamity to the state, and extraordinary sacrifices were offered in expiation.