Aphrodite’s Many Faces: Love, Power, and Devotion in Greek and Roman Mythology

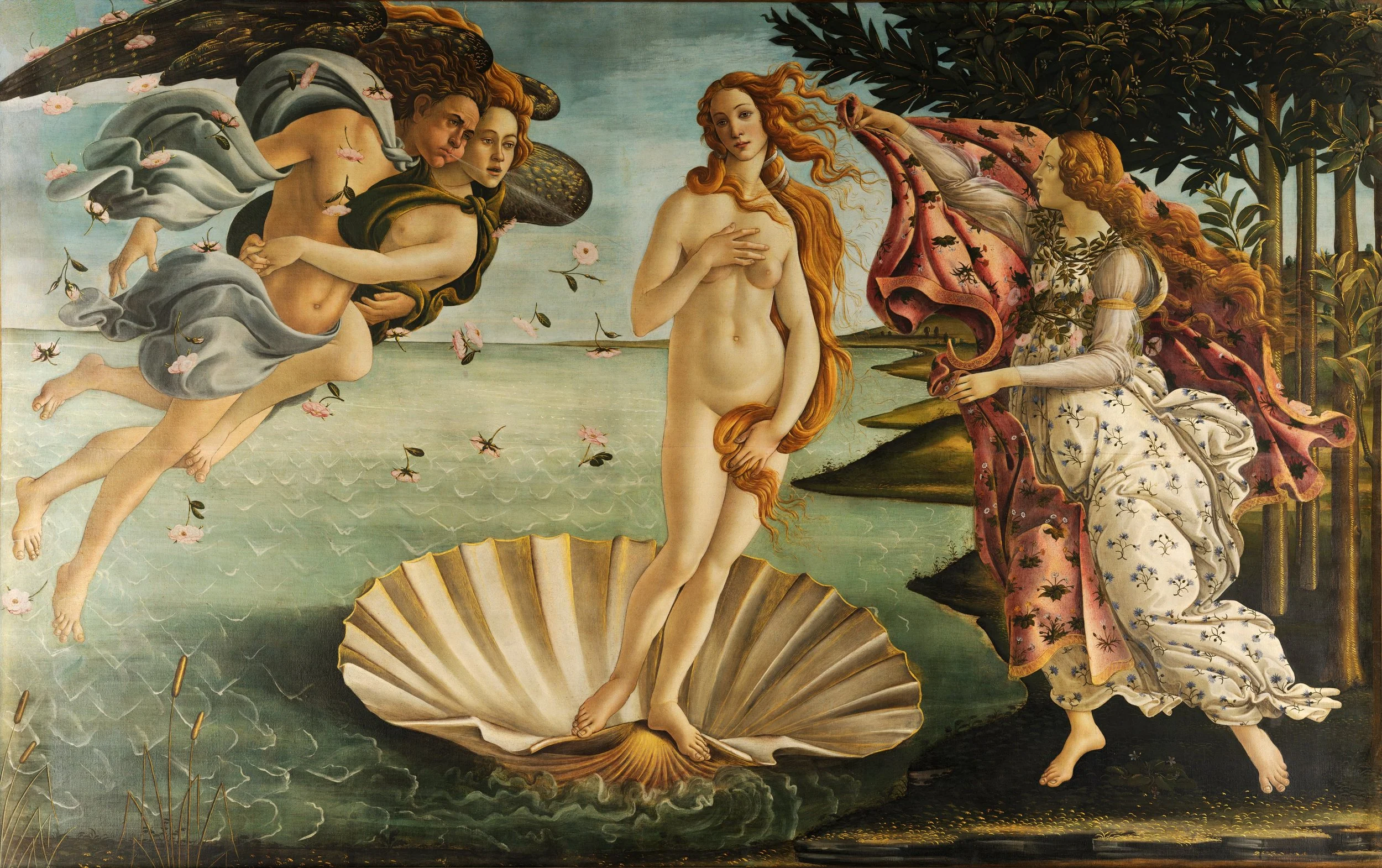

Sandro Botticelli's The Birth of Venus.

If love is the most inexhaustible of human concerns, it is also the most fraught. In mythology, love is never a mere emotion—it is a force, a weapon, a punishment, and, at times, a divine calamity. Nowhere is this clearer than in the ancient world’s vision of love as embodied by its gods. To the Greeks and Romans, love was presided over by a pantheon of deities, with Aphrodite (or Venus, as she was later called) at its head. Yet hers was not the only hand shaping human desire. Alongside her stood a cadre of lesser-known figures—Eros, Peitho, Hymenaios, and their Roman counterparts—each overseeing love’s subtleties, from flirtation to commitment, passion to betrayal.

Aphrodite, in her oldest conception, was not the tame, golden-haired muse of Renaissance paintings but something more elemental. Born from sea foam, as Hesiod tells it, she emerged from the severed genitals of Uranus, cast into the waves by his rebellious son Cronus. This birth—violent, primal—marks her as a goddess not just of beauty but of generative chaos. The Greeks saw in her an ambivalence: she could be a bringer of joy, uniting lovers in harmony, but just as often, she was a source of destruction. Consider Helen of Troy, whose fated love for Paris ignited a war, or Phaedra, driven by Aphrodite to desire her stepson, with disastrous consequences. Love, in the ancient imagination, was rarely benign.

The Romans, ever pragmatic, softened Venus’ sharper edges. She became a protector of marriage, an emblem of Rome itself. Her son, Cupid (the Latinized Eros), transformed from a mischievous primordial force into a cherubic bringer of romantic love. Where the Greeks had feared love’s capacity for upheaval, the Romans sought to harness it, embedding Venus within their civic and political structures. Julius Caesar traced his lineage to her, and Augustus promoted her as the mother of the Roman people, her divinity lending legitimacy to the empire. It was a striking transformation: a goddess of pleasure, desire, and disruption turned into a symbol of order and dynastic continuity.

But Aphrodite was never alone in shaping the realm of love. Peitho, the goddess of persuasion, stood beside her, for what is love without the art of seduction? Peitho’s influence extended beyond romance; she was invoked in political and rhetorical contexts, a reminder that persuasion itself is a kind of love—whether it be of ideas, power, or people. Hymenaios, a minor deity, presided over marriage, his name still echoing in the word “hymen” and in the cries of wedding processions. In contrast, Anteros, the god of requited love, existed to punish those who scorned affection, a spectral reminder that love, when unbalanced, could tip into cruelty.

There were also gods who embodied love’s darker shadows. Nemesis, goddess of retribution, ensured that excessive pride in one’s beauty or conquests was met with divine correction—Narcissus being the most famous victim. His tragic end, falling in love with his own reflection and wasting away from unfulfilled desire, was not merely a cautionary tale against vanity but a meditation on the self-consuming nature of love unreciprocated. And then there was Eris, goddess of discord, whose golden apple inscribed “for the fairest” incited the rivalry that led to the Trojan War. Even in love’s absence, there is strife.

Perhaps the most enigmatic figure in this landscape is Hecate, the chthonic goddess often associated with witchcraft and the crossroads of fate. While not typically classified as a love deity, she was invoked in love spells, a reminder that romance, in the ancient world, was often a matter of manipulation as much as genuine feeling. Ancient Greek love magic, recorded in surviving papyri, reveals an undercurrent of desperation—incantations, binding spells, and even curses used to force affection where it did not naturally arise. Love was not left to chance; it was something to be seized, controlled, or wrested from another’s will.

For all their grandeur, these deities were, ultimately, mirrors of human anxieties. The Greeks and Romans understood love not as a gentle force but as a volatile element, capable of bringing kingdoms to ruin as easily as it could unite them. In Aphrodite’s celestial beauty, in Cupid’s arrow, in Peitho’s whispered persuasions, they saw the whole spectrum of desire—from its most intoxicating pleasures to its most devastating consequences. That their myths endure is testament to love’s duality—its power to shape lives, histories, and civilizations, whether through devotion, longing, or, as often proved the case, destruction.