Yule-tide in England

BY

MARY P. PRINGLE and CLARA A. URANN

An excerpt from

YULE-TIDE IN MANY LANDS

1916

Introduction

Christmas has a rich history in England that spans centuries, with its traditions evolving over time. The celebration of Christmas as we know it now can be traced back to the medieval period when it was a time for feasting and merriment. During the Tudor era, Christmas became an elaborate affair with elaborate feasts, music, and traditional carols. However, the holiday underwent significant changes during the 17th century when the Puritans, led by Oliver Cromwell, viewed many Christmas customs as frivolous and banned the celebration of Christmas in the mid-1600s. This ban was lifted with the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, and Christmas once again became a popular and festive occasion. The Victorian era saw the revival of many Christmas traditions, thanks in part to Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, who popularized the Christmas tree. Charles Dickens' "A Christmas Carol" also played a significant role in shaping the modern image of Christmas as a time of generosity and goodwill.

Yule-tide in England

"Christians in old time did rejoice

And feast at this blest tide."

—Old Carol.

No country has entered more heartily into Yule-tide observance than England. From the earliest known date her people have celebrated this festival with great ceremony. In the time of the Celts it was principally a religious observance, but this big, broad-shouldered race added mirth to it, too. They came to the festivities in robes made from the skins of brindled cows, and wearing their long hair flowing and entwined with holly.

The Druids in the temples kept the consecrated fires burning briskly. All household fires were extinguished, and any one wishing to rekindle the flame at any time during the twelve days preceding Yule-tide must buy the consecrated fire. The Druids also had a rather unique custom of sending their young men around with Yule-tide greetings and branches of mistletoe (quiviscum). Each family receiving this gift was expected in return to contribute generously to the temples.

With the coming of the Saxons, higher revelry reigned, and a Saxon observance of Yule-tide must have been a jolly sight to see. In the center of the hall, upon the open hearth, blazed a huge fire with its column of smoke pouring out through an opening in the thatched roof, or, if beaten by the wind, wandering among the beams above. The usually large family belonging to the house gathered in this big living-room. The table stretched along one side of the room, and up and down its great length the guests were seated in couples. Between them was a half-biscuit of bread to serve as a plate. Later on this would be thrown into the alms-basket for distribution among the poor.

Soon the servers entered carrying long iron spits on which they brought pieces of the meats, fish, and fowls that had been roasted in isen pannas (iron pans) suspended from tripods out in the yard. Fingers were used instead of forks to handle the food, and the half-biscuit plates received the grease and juices and protected the handsome bord-cloth.

There was an abundance of food, for the Saxons were great eaters. Besides flesh, fish, and fowls their gardens furnished plenty of beans and other vegetables, and their ort-geards produced raspberries, strawberries, plums, sweet and sour apples, and cod-apples, or quinces. The cider and stronger drinks were quaffed from quaint round-bottomed tumblers which, as they could not stand up, had to be emptied at a draught.

The Saxons dined at about eleven o'clock and, as business was not pressing in those days, could well afford to spend hours at the feast, eating, drinking, and making merry.

After every one had eaten, games were played, and these games are the same as our children play to-day—handed down to us from the old Saxon times.

When night came and the ear-thyrls (eyeholes, or windows) no longer admitted the light of the sun, long candlesticks dipped in wax were lighted and fastened into sockets along the sides of the hall. Then the makers, or bards as they came to be called in later days, sang of the gods and goddesses or of marvelous deeds done by the men of old. Out-of-doors huge bonfires burned in honor of Mother-Night, and to her, also, peace offerings of Yule cakes were made.

It was the Saxon who gave to the heal-all of the Celts the pretty name of mistletoe, or mistletan,—meaning a shoot or tine of a tree. There was jollity beneath the mistletoe then as now, only then everybody believed in its magic powers. It was the sovereign remedy for all diseases, but it seems to have lost its curative power, for the scientific men of the present time fail to find that it possesses any medical qualities.

Later on, when the good King Alfred was on the English throne, there were greater comforts and luxuries among the Saxons. Descendants of the settlers had built halls for their families near the original homesteads, and the wall that formerly surrounded the home of the settler was extended to accommodate the new homes until there was a town within the enclosure. Yule within these homes was celebrated with great pomp. The walls of the hall were hung with rich tapestries, the food was served on gold and silver plates, and the tumblers, though sometimes of wood or horn, were often of gold and silver, too.

In these days the family dressed more lavishly. Men wore long, flowing ringlets and forked beards. Their tunics of woolen, leather, linen, or silk, reached to the knees and were fastened at the waist by a girdle. Usually a short cloak was worn over the tunic. They bedecked themselves with all the jewelry they could wear; bracelets, chains, rings, brooches, head-bands, and other ornaments of gold and precious stones.

Women wore their best tunics made either of woolen woven in many colors or of silk embroidered in golden flowers. Their "abundant tresses," curled by means of hot irons, were confined by the richest head-rails. The more fashionable wore cuffs and bracelets, earrings and necklaces, and painted their cheeks a more than hectic flush.

In the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries the magnificence of the Yule-tide observance may be said to have reached its height. In the old baronial halls where:

"The fire, with well-dried logs supplied,

Went roaring up the chimney wide,"

Christmas was kept with great jollity.

It was considered unlucky to have the holly brought into the house before Christmas Eve, so throughout the week merry parties of young people were out in the woods gathering green boughs, and on Christmas Eve, with jest and song, they came in laden with branches to decorate the hall.

"Lo, now is come our joyfull'st feast!

Let every man be jolly,

Eache room with yvie leaves be drest.

And every post with holly."

Later on, men rolled in the huge Yule-log, emblematic of warmth and light. It was of oak if possible, the oak being sacred to Thor, and was rolled into place amidst song and merriment. In one of these songs the first stanza is:

"Welcome be thou, heavenly King,

Welcome born on this morning,

Welcome for whom we shall sing,

Welcome Yule."

The third stanza is addressed to the crowd:

"Welcome be ye that are here,

Welcome all, and make good cheer,

Welcome all, another year;

Welcome Yule."

Each member of the family, seated in turn upon the log, saluted it, hoping to receive good luck. It was considered unlucky to consume the entire log during Yule; if good luck was to attend that household during the coming twelve months, a piece ought to be left over with which to start the next year's fire.

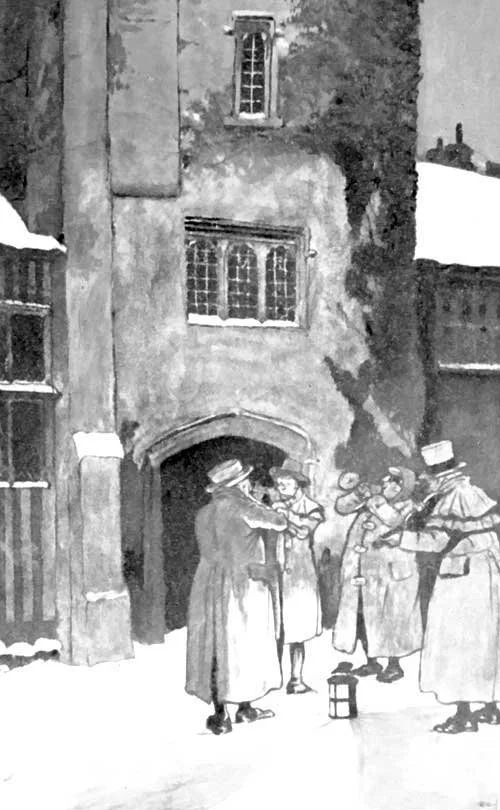

Serenaded by the Waits.

"Part must be kept wherewith to tende

The Christmas log next yeare,

And where 'tis safely kept, the fiend

Can do no mischiefe theere."

The boar's head held the principal place of honor at the dinner. So during September and October, when the boar's flesh was at its best, hunters with well-trained packs of boar-hounds set out to track this savage animal. They attacked the boar with spears, or surrounded him and drove him into nets. He was a ferocious antagonist to both dogs and men, and when sore pressed would wheel about, prepared to fight to the death. Before the dogs could grip him by the ear, his one weak point, and pin him down, his sharp teeth would often wound or even kill both the hunter and his dogs. The pluckier the animal the louder the praise sung in his honor when his head was brought into the hall. The great head, properly soused, was borne in on an immense salver by the "old blue-coated serving-man" on Christmas day. He was preceded by the trumpeters and followed by the mummers, and thus in state the boar's head was ushered in and assigned to its place on the table. The father of the family or head of the household laid his hand on the dish containing the "boar of atonement," as it was at one time called, swearing to be faithful to his family and to fulfil all his obligations as a man of honor. This solemn act was performed before the carving by every man present. The carver had to be a man of undaunted courage and untarnished reputation.

Next in honor at the feast was the peacock. It was sometimes served as a pie with its head protruding from one side of the crust and its wide-spread tail from the other; more often the bird was skinned, stuffed with herbs and sweet spices, roasted, and then put into its skin again, when with head erect and tail outspread it was borne into the hall by a lady—as was singularly appropriate—and given the second place on the table.

The feudal system gave scope for much magnificence at Yule-tide. At a time when several thousand retainers[1] were fed daily at a single castle or on a baron's estate, preparations for the Yule feast—the great feast of the year—were necessarily on a large scale, and the quantity of food reported to have been prepared on such occasions is perfectly appalling to Twentieth-Century feasters.

Massinger wrote:

"Men may talk of Country Christmasses,

Their thirty-pound butter'd eggs, their pies of carp's tongue,

Their pheasants drench'd with ambergris, the carcasses

Of three fat wethers bruis'd for gravy, to

Make sauces for a single peacock; yet their feasts

Were fasts, compared with the City's."

In 1248 King Henry III held a feast in Westminster Hall for the poor which lasted a week. Four years later he entertained one thousand knights, peers, and other nobles, who came to attend the marriage of Princess Margaret with Alexander, King of the Scots. He was generously assisted by the Archbishop of York who gave £2700, besides six hundred fat oxen. A truly royal Christmas present whether extorted or given of free will!

More than a century later Richard II held Christmas at Litchfield and two thousand oxen and two hundred tuns of wine were consumed. This monarch was accustomed to providing for a large family, as he kept two thousand cooks to prepare the food for the ten thousand persons who dined every day at his expense.

Henry VIII, not to be outdone by his predecessors, kept one Yule-tide at which the cost of the cloth of gold that was used alone amounted to £600. Tents were erected within the spacious hall from which came the knights to joust in tournament; beautiful artificial gardens were arranged out of which came the fantastically dressed dancers. The Morris (Moresque) Dance came into vogue in England during the reign of Henry VII, and long continued to be a favorite. The dancers were decorated from crown to toe in gay ribbon streamers, and cut all manner of antics for the amusement of the guests. This dance held the place at Yule that the Fool's Dance formerly held during the Roman Saturnalia.

Henry VIII's daughter, Elizabeth, kept the season in great magnificence at Hampton Court where plays written for the occasion were presented. The poet Herrick favored:

"Of Christmas sports, the wassell boule,

That's tost up after Fox-i-th'-hole."

This feature of Yule observance, which is usually attributed to Rowena, daughter of Vortigern, dates back to the grace-cup of the Greeks and Romans which is also the supposed source of the bumper. According to good authority the word bumper came from the grace-cup which Roman Catholics drank to the Pope, au bon Père. The wassail bowl of spiced ale has continued in favor ever since the Princess Rowena bade her father's guests Wassheil.

The offering of gifts at Yule has been observed since offerings were first made to the god Frey for a fruitful year. In olden times one of the favorite gifts received from tenants was an orange stuck with cloves which the master was to hang in his wine vessels to improve the flavor of the wine and prevent its moulding.

As lords received gifts from their tenants, so it was the custom for kings to receive gifts from their nobles. Elizabeth received a goodly share of her wardrobe as gifts from her courtiers, and if the quality or quantity was not satisfactory, the givers were unceremoniously informed of the fact. In 1561 she received at Yule a present of a pair of black silk stockings knit by one of her maids, and never after would she wear those made of cloth. Underclothing of all kinds, sleeves richly embroidered and bejeweled, in fact everything she needed to wear, were given to her and she was completely fitted out at this season.

In 1846 Sir Henry Cole is said to have originated the idea of sending Christmas cards to friends. They were the size of small visiting-cards, often bearing a small colored design—a spray of holly, a flower, or a bit of mistletoe—and the compliments of the day. Joseph Crandall was the first publisher. Only about one thousand were sold the first year, but by 1862 the custom of sending one of these pretty cards in an envelope or with gifts to friends became general and has now spread to other countries.

During the Reformation the custom of observing Christmas was looked upon as sacrilegious. It savored of popery, and in the narrowness of the light then dawning the festival was abolished except in the Anglican and Lutheran Churches. Tenants and neighbors no longer gathered in the hall on Christmas morning to partake freely of the ale, blackjacks, cheese, toast, sugar, and nutmeg. If they sang at all, it was one of the pious hymns considered suitable-and sufficiently doleful—for the occasion. One wonders if the young men ever longed for the sport they used to have on Christmas morning when they seized any cook who had neglected to boil the hackin[2] and running her round the market-place at full speed attempted to shame her of her laziness.

Protestants were protesting against the observance of the day; Puritans were working toward its abolishment; and finally, on December 24, 1652, Parliament ordered "That no observance shall be had of the five and twentieth day of December, commonly called Christmas day; nor any solemnity used or exercised in churches upon that day in respect thereof."

Then Christmas became a day of work and no cheer. The love of fun which must find vent was expended at New Year, when the celebration was similar to that formerly observed at Christmas. But people were obliged to bid farewell to the Christmas Prince who used to rule over Christmas festivities at Whitehall, and whose short reign was always one of rare pleasure and splendor. He and other rulers of pastimes were dethroned and banished from the kingdom. Yule cakes, which the feasters used to cut in slices, toast, and soak in spicy ale, were not to be eaten—or certainly not on Christmas. It was not even allowable for the pretty Yule candles to be lighted.

Christmas has never regained its former prestige in England. Year after year it has been more observed in churches and families, but not in the wild, boisterous, hearty style of olden times. Throughout Great Britain Yule-tide is now a time of family reunions and social gatherings. Ireland, Scotland, Wales, and the Islands each retain a few of their own peculiar customs, but they are not observed to any extent. In Ireland—or at least in some parts—they still indulge in drinking what is known as Lamb's-wool, which is made by bruising roasted apples and mixing the juice with ale or milk. This drink, together with apples and nuts, is considered indispensable on Christmas Eve.

England of all countries has probably known the merriest of Yule-tides, certainly the merriest during those centuries when the mummers of yore bade to each and all

"A merry Christmas and a happy New Year,

Your pockets full of money and your cellar full of beer."

There seems always to have been more or less anxiety felt regarding New Year's Day in England, for "If the morning be red and dusky it denotes a year of robberies and strife."

"If the grass grows in Janivear

It grows the worse for 't all the year."

And then very much depended upon the import of the chapter to which one opened the Bible on this morning. If the first visitor chanced to be a female, ill luck was sure to follow, although why it should is not explained.

It was very desirable to obtain the "cream of the year" from the nearest spring, and maidens sat up till after midnight to obtain the first pitcherful of water, supposed to possess remarkable virtues. Modern plumbing and city water-pipes have done away with the observance of the "cream of the year," although the custom still prevails of sitting up to see the Old Year out and the New Year in.

There was also keen anxiety felt as to how the wind blew on New Year's Eve, for

"If New Year's Eve night wind blow South,

It betokeneth warmth and growth;

If West, much milk, and fish in the sea;

If North, much cold and storm there will be;

If East, the trees will bear much fruit;

If Northeast, flee it man and brute."

-

[1] The Earl of Warwick had some thirty thousand.

[2] Authorities differ as to whether this was a big sausage or a plum pudding.