The Case of Anne Boleyn

Photo: Baran Lotfollahi

BY

C. MacLaurin

An excerpt from

POST MORTEM:

ESSAYS, HISTORICAL AND MEDICAL

1922

Introduction

Henry VIII's desire to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon and marry Anne Boleyn was a catalyst for the English Reformation, as he broke with the Roman Catholic Church and established the Church of England. However, Anne's inability to bear a son, along with her political enemies, ultimately led to her downfall. She was accused of adultery, incest, and treason and was beheaded in 1536. Despite her tragic end, Anne Boleyn remains an intriguing figure of the Tudor era, with many debates and controversies surrounding her life and legacy.

The Case of Anne Boleyn

There is something Greek, something akin to Œdipus and Thyestes, in the tragedy of Anne Boleyn. It is difficult to believe, as we read it, that we are viewing the actions of real people subject to passions violent indeed yet common to those of mankind, and not the creatures of a nightmare. Yet I believe that the conduct of the three protagonists, Henry, Catherine, and Anne, can all be explained if we appreciate the facts and interpret them with the aid of a little medical knowledge and insight. Let us search for this explanation. Needless to say we shall not get it in the strongly Bowdlerized sketches that most of us have learnt at school; it is a pity that such rubbish should be taught, because this period is one of the most important in English history; the actors played vital parts; and upon the drama that they played has depended the history of England ever since.

In considering an historical drama one has to remember the curtain of gauze which Time has drawn before us, and to allow for its colour and density. In the case of Henry VIII and his time, though the actual materials are enormous, yet everything has to be viewed through an odium theologicum that is unparalleled since the days of Theodora. In the eyes of the Catholics, Henry was, if not the actual devil incarnate, at all events the next thing; and their opinion has survived among many people who ought to know better to the present day. Decidedly we must make a great deal of allowance.

Henry succeeded to the throne, nineteen years of age, handsome, rather free-living, full of joie-de-vivre, charming, and with every promise of greatness and happiness. He died at fifty-five, unhappy, worn down with illness, at enmity with his people, with the Church, and with the world in general, leaving a memory in the popular mind of a murderous concupiscence that has become a byword. About the time that he was a young man, syphilis, which is supposed to have been introduced by Columbus’ men, ran like a whirlwind through Europe. Hardly anyone seems to have escaped, and it was said that even the Pope upon the throne of St. Peter went the way of most other people, though it is possible that this accusation was as unreliable as many other accusations against the popes. Be that as it may, the foundations were then laid for that syphilization which has transformed the disease into its present mildness. It is impossible to doubt that Henry contracted it in his youth; the evidence will become clear to any doctor as we proceed.

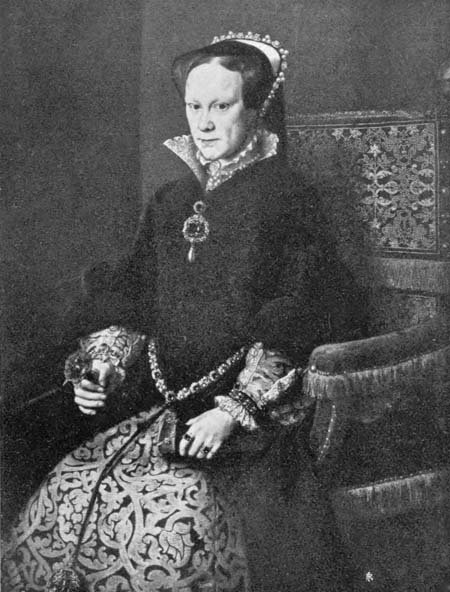

The first act of his reign was to marry for political reasons Catherine of Aragon, who was the widow of his elder brother Arthur. She was daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain, and, though far from beautiful, proved herself to possess a great and noble soul and a courage of well-tempered steel. The English people took her to their hearts, and when unmerited misfortune fell upon her never lost the love they had felt for her when she was a happy young woman. Though she was six years older than Henry, the two lived happily together for many years. Seven months after marriage Catherine was delivered of a daughter, still-born. Eight months later she had a son, who lived three days. Two years later she had a still-born son. Nine months later she had a son, who died in early infancy, and eighteen months afterwards the infant was born who was to live to be Queen Mary. Henry was intensely disappointed, and for the first time turned against his wife. It was all important to produce an heir to the throne, for it was thought that no woman could rule England. No woman had ever ruled England, save only Matilda, and her precedent was not alluring. So Henry longed desperately for a son; nevertheless as the little Mary grew up—a sickly child—he became passionately devoted to her. She grew up, as one can see from her well-known portrait, probably an hereditary syphilitic. For a time Henry had thought of divorcing Catherine, but his affection for Mary probably turned the scale in her mother’s favour. Catherine had several more miscarriages, and by the time she was forty-two ceased to menstruate; it became clear that she would have no more children and could never produce an heir to the throne.

Mary Tudor from a portrait by Moro Antonio (Madrid, Prado).

During these years Henry’s morals had been no worse than those of any other prince in Europe; certainly better than Louis XIV and XV, who were to come after him, or Charles II. He met Mary Boleyn, daughter of a rich London merchant, and made her his mistress. Later on he met Anne Boleyn, her sister, a girl of sixteen, and fell in love. We have a very good description of her, and several portraits. She was of medium stature, not handsome, with a long neck, wide mouth, bosom “not much raised,” eyes black and beautiful and a knowledge of how to use them. Her hair was long, and it appears that she used to wear it long and flowing in the house. It was not so very long since Joan of Arc had been burnt largely because she went about without a wimple, and Mistress Anne’s conduct with regard to her hair was probably worse in those days than for a girl to be seen smoking cigarettes when driving a motor-car to-day. At any rate, she acquired demerit by it, and everybody was on the look-out for more serious false steps. The truth seems to be—so far as one can ascertain truth from reports which, even if unprejudiced, came from people who knew nothing about a woman’s heart—that she was a bold and ambitious girl who laid herself out to capture Henry, and succeeded. Mary Boleyn was thrust aside, and Henry paid violent court in his own enormous and impassioned way to Anne. We have some of his love letters; there can be no doubt of his sincerity, or that his love for Anne was, while it lasted, the great passion of his life. Had she behaved herself she might have retained that love. She repulsed him for several years, and we can see the idea of divorce gradually growing in his mind. He appealed to Pope Clement VII to help him. Catherine defended herself bravely, and stirred Europe in her cause. The Pope hesitated, crushed between the hammer and the anvil, between Henry and the Emperor Charles V. Henry discovered that his marriage with Catherine had come within the prohibited degrees, and that she had never been his wife at all. It was a matter of doubt then—and I believe still is—whether the Pope’s dispensation could acquit them of mortal sin. Apparently even his Holiness’ influence would not have been sufficient to counterbalance the crime of marrying his deceased brother’s widow; nevertheless it was rather remarkable that, if Henry were really such a stickler for the forms of canon law as he now wished to make out, he never troubled to raise the question until after he had fallen in love with some one else. He definitely promised Anne that he would divorce Catherine, marry Anne, and make her Queen of England. Secure in his promise, Anne yielded to her lover, seeing radiant visions of glory before her. How foolish would any girl be who let slip the chance—nay, the certainty—of being the Queen! Yet she was to discover that even queens can be bitterly unhappy. Anne sprang joyfully into the unknown, as many a girl has done before her and since, trusting to her power to charm her lover; and became pregnant. Meanwhile the struggle for the divorce proceeded, the Pope swaying this way and that, and Catherine defending her honour and her throne with splendid courage. The nurses and astrologers declared that the fœtus was a son, and the lovers, mad with joy, were married in secret, divorce or no divorce. The obliging Archbishop Cranmer pronounced that the marriage with Catherine was null and void, as the Pope would not do so.

The time came for Anne to fulfil her promise and provide an heir. King and queen anticipated the event in the wildest excitement. There had been several lovers’ quarrels, which had been made up in the usual manner; once Henry was heard to say passionately that he would rather beg his bread in the streets than desert her. Yet it is doubtful whether Anne Boleyn was ever anything more than an ambitious courtesan; it is doubtful whether she ever felt anything towards him but her natural wish to be queen. In due course her baby was born, and it was a girl—the girl who afterwards became Queen Elizabeth.

Henry’s disappointment was tragic, and for the first time Anne began to realize the terror of her position. She was detested by the people and the Court, who were emphatically on the side of the noble woman whom she had supplanted. She had estranged everybody by her vain-glory and arrogance in the hour of her triumph; and it began to be whispered that even if her own marriage were legal while Catherine was still alive, yet it was illegal by the canon law, for Mary Boleyn, her sister, had been Henry’s wife in all but name. Canonically speaking, Henry had done no better by marrying her than by marrying Catherine. A horrible story went around that he had been familiar with her mother first, and that Anne was his own daughter, and moreover that he knew it. I think we can definitely and at once put this aside as an ecclesiastical lie; there is absolutely no evidence for it and it is impossible to conceive two persons more unlike than the little lively brunette and the great fresh-faced “bluff King Hal.” Moreover, Henry denied the story absolutely, and whatever else he was, he was a man who was never afraid to tell the truth. Most of the difficulties in understanding this complex period of our history disappear if we believe Henry’s own simple statements; but these suffer from the incredulity which Bismarck found three hundred years later when he told his rivals the plain unvarnished truth.

Let us anticipate events a little and narrate the death of Catherine, which took place in 1536, nearly three years after the birth of Elizabeth. The very brief and sketchy accounts which have survived give me the impression that she died of uræmia, but no definite opinion can be given. Henry, of course, lay under the immediate charge of having poisoned her, but I do not know that anybody believed it very seriously. So died this unhappy and well-beloved lady, to whom life meant little but a series of bitter misfortunes.

After Elizabeth was born the tragedy began to move with terrible impetus towards its climax. Henry developed an intractable ulcer on his thigh, which persisted till his death, and frequently caused him severe agony whenever the sinus closed. He became corpulent, the result of over-eating and over-drinking. He had been immensely worried for years over the affair of Catherine; as a result his blood-pressure seems to have risen, so that he was affected by frightful headaches, which often incapacitated him from work for days together. He gave up the athleticism which had distinguished his resplendent youth, aged rapidly, and became a harassed, violent, ill-tempered middle-aged man—not at all the sort of man to turn into a cuckold.

Yet this is precisely what Anne did. Less than a month after Elizabeth was born—while she was still in the puerperal state—she solicited Sir Henry Norreys, the most intimate friend of the King, to be her lover. A week later, on October 17th, 1533, he yielded. During the next couple of years Anne seems to have gone absolutely out of her senses, if the contemporary stories are true. She seems to have solicited several prominent men of the Court, and even to have stooped to one of the musicians; worst of all, it was said that she had committed incest with her brother, Lord Rocheford. Nor did she behave with the ordinary consideration for the feelings of others that might have brought her hosts of friends—remember, she was a queen!—should the time ever come when she should need them. It does not require any great amount of civility on the part of a queen to win friends. Arrogant and overbearing, she estranged everybody at Court; she acted like a beggar on horseback, and was left without a friend in the place. And she, who owed her husband such a world, behaved towards him with the same arrogance as she showed to others, and in addition jealousy both concerning other women whom she feared and concerning the King’s beloved daughter, Mary. She spoke to the Duke of Norfolk—her uncle on the mother’s side, and one of the greatest peers of the realm—“like a dog”; as he turned away he muttered that she was “une grande putaine.” The most polite interpretation of the French word is “strumpet.” When the Duke used such a word to his own niece, what sort of reputation must have been gathering about her?

She had two more miscarriages. After the second the King’s fury flamed out, and he told her plainly that he deeply regretted having married her. He must have indeed been sorry; he had abandoned a good woman for a bad; for her he had quarrelled with the Pope and with many of his subjects; whatever conscience he had must have been tormenting him: all these things for the sake of an heir, which seemed as hopelessly unprocurable as ever. Both the women seemed affected by some fate which condemned them to perpetual miscarriages; this fate, of course, was Henry’s own syphilis, even supposing that neither wife had contracted it independently. (It is much to Anne Boleyn’s credit or discredit, that to a syphilitic husband she bore a daughter so vigorous as Elizabeth, though Professor Chamberlin does not appear to think very highly of her health.)

Meanwhile all sorts of scandalous rumours were flying about; and finally a maid of honour, whose chastity had been impugned, told a Privy Councillor that no doubt she herself was no better than she should be, but that at any rate her Majesty Queen Anne was far worse. The Privy Councillor related this to Thomas Cromwell; he, the rumours being thus focussed, dared to tell the King. Henry changed colour, and ordered a secret inquiry to be held. At this inquiry the ladies of the bedchamber were strictly cross-examined, but nothing was allowed to happen for a few days, when a secret commission was appointed, consisting of the Chancellor, the judges, Thomas Cromwell, and other members of the Council. Sir William Brereton was first sent to the Tower, then the musician Smeaton. Next day there was a tournament at Greenwich, in the midst of which Henry suddenly rose and left the scene, taking Norreys with him. Anne was brought before the Commission next day, and committed to the Tower, where she found that Sir Francis Weston had preceded her. Lord Rocheford, her brother, joined her almost immediately on the charge of incest.

The Grand Juries of Kent and Middlesex returned true bills on the cases, and the Commission drew up an indictment, giving names, places, and dates for every alleged act. The four commoners were put on trial at Westminster Hall. Anne’s father, Lord Wiltshire, though he volunteered to sit, was excused attendance, since a verdict of guilty against the men would necessarily involve his daughter. One may read this either way, against or in favour of Anne. Either Wiltshire was enraged at her folly, and merely wished to end her disgrace; or it may be that he thought he would be able to sway the Court in her favour. Possibly he was afraid of the King and wished to show that he at least was on his royal side, however badly Anne may have behaved. In dealing with a harsh and tyrannical man like Henry VIII it is difficult to assess human motives, and one prefers to think that Wiltshire was trying to do his best for his daughter. Smeaton the musician confessed under torture; the other three protested their innocence, but were found guilty and were sentenced to death. Thomas Cromwell, in a letter, said that the evidence was so abominable that it could not be published. Evidently the Court of England had suddenly become squeamish.

Anne was next brought to trial before twenty-five peers of the realm, her uncle the Duke of Norfolk being in the chair. Probably, if the story just related were true, the Duke’s influence would not be exerted very strongly in her favour, and she was convicted and sentenced to be hanged or burnt at the King’s pleasure; her brother was tried separately and also convicted. It is said that her father and uncle concurred in the verdict; they may have been afraid of their own heads. On the other hand, it is possible that Anne was really guilty; unfortunately the evidence has perished. The five men were executed on Tower Hill in the presence of the woman, whose death was postponed from day to day. In the meantime Henry procured his divorce from her, while Anne, in a state of violent hysteria, continuously protested her innocence. On the night before her execution she said that the people would call her “Queen Anne sans tête,” laughing wildly as she spoke; if one pronounces these words in the French manner, without verbal accent, they form a sort of jingle, as who should say “ta-ta-ta-ta”; and this foolish jingle seems to have run in her head, as she kept repeating it all the evening; and she placed her fingers around her slender neck—almost her only beauty—saying that the executioner would have little trouble, as though it were a great joke. These things were put to the account of her light and frivolous nature, and have probably weighed heavily with posterity in attempting to judge her case; but it is clear that they were merely manifestations of hysteria. Joan of Arc, whose character was probably the direct antithesis of Anne Boleyn’s, laughed when she heard the news of her reprieve. Some people think she laughed ironically, as though a very simple peasant-girl could be ironical if she tried. Irony is a quality of the higher intelligence. But cannot a girl be allowed to laugh hysterically for joy? Or cannot Anne Boleyn be allowed to laugh hysterically for grief and terror without being called light and frivolous? So little did her contemporaries understand the human heart. A few years later came one Shakespeare, who could have told King Henry differently; and the extraordinary burgeoning forth of the English intellect in William Shakespeare is one of the most wonderful things in our history. Before the century had terminated in which Anne Boleyn had been considered light and frivolous because she had laughed in the shadow of the block, Shakespeare had plumbed the depths of human nature.

Anne was beheaded on May 19th, 1536, in the Tower, on a platform covered thickly with straw, in which lay hidden a broadsword. The headsman was a noted expert brought over specially from St. Omer, and he stood motionless among the gentlemen onlookers until the necessary preliminaries had been completed. Then, Anne kneeling in prayer and her back being turned towards him, he stole silently forward, seized the sword from its hiding-place, and severed her slender neck at a blow. As she had predicted, he had little trouble, and she never saw either her executioner or the sword that slew her. Her body and severed head were bundled into a cask, and were buried within the precincts of the Tower; and Henry threw his cap into the air for joy. On the same day he obtained a special dispensation to marry Jane Seymour. He married her next day.

The chief authority for the reign of Henry VIII is contained in the Letters and Papers of the Reign of Henry VIII, edited by Brewer and Gairdner. This gigantic work, containing more than 20,000 closely printed pages, is probably the greatest monument of English scholarship; the prefaces to the different volumes are remarkable for their learning and delightful literary style. Froude’s history is charming and brilliant as are all his writings, but is now rather out of date, and is marred by his hero-worship of Henry and his strong Protestant bias. He sums up absolutely against Anne, and, after reading the letters which he publishes, I do not see how he could have done anything else. He believes her innocent of incest, however, and doubtless he is right. Let us acquit her of this crime, at any rate. A. F. Pollard’s Life of Henry VIII is meticulously accurate, and is charmingly written; he thinks it impossible that the juries could have found against her and the court have convicted without the strongest evidence, which has not survived. P. C. Yorke sums up rather against her in the Encyclopædia Britannica; but S. R. Gardiner thinks the charges too horrible to be believed and that probably her own only offence was that she could not bear a son. Professor Gardiner had evidently seen little of psychological medicine, or he would have known that no charge is too horrible to believe. The “Unknown Spaniard” of the Chronicle of Henry VIII is an illiterate fellow enough, but no doubt of Anne’s guilt appears to enter his artless mind; he probably represents the popular contemporary view. He says that he took his stand in the ring of gentlemen who witnessed the execution. He gives an account of the arrest of Sir Thomas Wyatt the poet—the first English sonneteer—and the ipsissima verba of a letter which Wyatt wrote to Henry, narrating how Anne had solicited him even before her marriage in circumstances that rendered her solicitation peculiarly brazen and shameless. That Henry should have pardoned him seems to show that the real crime of Anne was that she had contaminated the blood royal; a capital offence in a queen in almost all ages and almost every country. Before she became a queen Henry was probably complaisant enough to Anne’s peccadilloes; but afterwards—that was altogether different. “There’s a divinity doth hedge” a queen!

Lord Herbert of Cherbury, writing seventy years later, narrates the ghastly story with very little feeling one way or the other. Apparently the legend of Anne’s innocence and Henry’s blood-lust had not yet arisen. The verdict of any given historian appears to depend upon whether he favours the Protestants or the Catholics. Speaking as a doctor with very little religious preference one way or the other, the following considerations appeal strongly to myself. If Henry wished to get rid of a barren wife—barren through his own syphilis!—as he undoubtedly did, then Mark Smeaton’s evidence alone was enough to hang any queen in history from Helen downward, especially if taken in conjunction with the infamous stories related by the “Unknown Spaniard.” Credible or not, these stories show the reputation that attached to the plain little Protestant girl who could not provide an heir to the throne—the sort of reputation which mankind usually attaches to a woman who, by unworthy means, has attained to a high position. Why should the King and Cromwell, both exceedingly able men, gratuitously raise the questions of incest and promiscuity and send four innocent men to their deaths absolutely without reason? Why should they raise all the tremendous family ill-will and public reprobation which such an act of bloodthirsty tyranny would have caused? Stern as they were they never showed any sign of mere blood-lust at any other time; and the facts that Anne’s father and uncle both appear to have concurred in the verdict, and that, except for her own denial, there is not a word said in her favour, seems to require a great deal of explanation.

We can thoroughly explain her conduct by supposing that she was afflicted by hysteria and nymphomania. There are plenty of accounts of unhappy women whose cases are parallel to Anne’s in the works of Havelock-Ellis and Kisch. There is plenty of indubitable evidence that she was hysterical and unbalanced, and that she passionately longed for a son; and it is simpler to believe her the victim of a well-known and common disease than that we should suppose the leading statesmen of England and nearly the whole of its peerage suddenly to be affected with blood-lust. It has been suggested thatAnne, passionately longing for a son and terrified of her husband’s tyrannical wrath, acted like one of Thomas Hardy’s heroines centuries later and tried another lover in the hope that she would gratify her own and Henry’s wishes. This course of procedure is probably not so uncommon as some husbands imagine and would satisfy the questions of our problem but for Anne’s promiscuity and vehemence in solicitation. If her sole object in soliciting Norreys was to provide a son, why should she have gone from man to man till the whole Court seems to have been ringing with her ill fame?

Her spasms of violent temper after her marriage, her fits of jealousy, her foolish arrogance and insolence to her friends, are all mental signs which go with nymphomania, and the fact that her post-nuptial incontinence seems to have begun while she was still in the puerperal state after the birth of her only living child seems highly significant. It is not uncommon for sexual desire to become intolerable in nervous and puerperal women. The proper place for Anne Boleyn was a mental hospital.

Henry VIII’s case, along with those of his children, deserve a paper to themselves. Henry himself died of neglected arterio-sclerosis just in the nick of time to save the lives of better men from the executioner; Catherine Parr, who married him probably in order to nurse him—it is possible that she was really fond of him and that there was even then something attractive about him—succeeded in outliving him by a remarkable effort of diplomatic skill and courage, though had Henry awakened from his uræmic stupor probably her head would have been added to his collection. On the whole, one cannot avoid the conclusion that his conduct to his wives was not all his fault. They seem to have done no credit to his power of selection. The first and the last appear to have been the best, considered as women.

Inexorable Nemesis had avenged Catherine. The worry of the divorce left her husband with an arterial tension which, added to the royal temper, caused great misery to England and ultimately death to himself; and her mean little rival lay huddled in the most frightful dishonour that ever befell a woman. Decidedly there is something Greek in the complete horror of the tragedy.