Jason and Medea: Is there a Sex War?

Hypatia, or Woman and Knowledge

Dora Russell

1925

Medea: Or the wedding of Jason and Creusa by Rembrandt van Rijn.

“Hypatia was a University lecturer denounced by Church dignitaries and torn to pieces by Christians. Such will probably be the fate of this book: therefore it bears her name. What I have written here I believe, and shall not retract or change for similar episcopal denunciations.”

A feature of modern life is that matrimonial quarrels, like modern war, are carried on on a large scale, involving not individuals, nor even small groups of individuals, but both sexes and whole classes of society.

In the past, Jason and Medea, neither of them quite an exemplary character, measured their strength against one another as individuals; and, though each voiced the wrongs and the naked brutality of their sex, it did not occur to either to seek in politics or in social reform a solution or a compromise. Jason, indeed, as the reactionary face to face with a turbulent and insurgent female, called to his aid the powers of kingship and the State—to suppress and exile, but not to remedy. Medea, driven mad—like so many able and remarkable women—by the contempt and ingratitude of men as individuals or in the mass, and aware that the law was a mockery where she was concerned, expressed herself in savage protest after the manner of a militant suffragette. While I can open my newspaper to-day and read of mothers desperate with hunger, misery, or rage drowning themselves and their children, I cannot bring myself to look upon Medea as some elemental being from a dark and outrageous past. As for Jason, he never did appear to anybody as other than an ordinary male.

During the last twenty or twenty-five years, when women were struggling for their right as citizens to a vote and to a decent education, began what has been called the sex war. No woman would deny that we began it, in the sense that we were rebels against a system of masculine repression which had lasted almost unbroken since the beginning of history. In a similar sense, the proletarian to-day begins the class war. Those who remember the heroic battles of suffrage days know that the sequence of events was as follows: We made our just demands and were met with ridicule. We followed with abuse—all the pent-up anger, misery, and despair of centuries of thwarted instinct and intelligence. Man retaliated with rotten eggs. We replied with smashed windows; he with prison and torture. People forget so readily, that it is well to remember that this was in the immediate past; it is not a nightmare picture of one of those future sex wars with which our modern Jasons delight to terrify the timorous of both sexes.

From Italian Front X (ca. 1914-1918) by Dezider Czölder.

Is there a sex war? There has been. It was a disgraceful exhibition, and would not have come to a truce so soon, but that it was eclipsed by the still more disgraceful exhibition of the European War. In 1918 they bestowed the vote, just as they dropped about a few Dames and M.B.E.’s, as a reward for our services in helping the destruction of our offspring. Had we done it after the fashion of Medea, the logical male would have been angry. They gave the vote to the older women, who were deemed less rebellious. Such is the discipline of patriotism and marriage, as it is understood by most women, that the mother will sacrifice her son with a more resigned devotion than the younger woman brings to the loss of her lover. There may be more in this than discipline. If honesty of thought, speech, and action were made possible for women, it might transpire that on the average a woman’s love for her mate is more compelling than love for her offspring. Maternal instinct—genuine, not simulated—is rarer, but, when found, more enduring.

There was a promise, as yet unredeemed by any political party—for the politician has yet to be found who will realize that the sex problem is as fundamental in politics as the class war, and more fundamental than foreign trade and imperial expansion—to extend this franchise on equal terms with men. “Good fellowship” between the sexes as between classes was the key-note of the war. It was held that women had proved their mettle and that mutual aid was to be the basis of all future activities, public and private. The sex question was deemed settled, and everyone was led to suppose that all inequalities would be gradually eliminated. On this partial victory and this promise feminists called a truce, and abandoned the tactics of militarism.

But you never know where you have Jason. He was a soldier, mark you, and a gentleman. Forbidden open warfare, he takes to sniping. He snipes the married women out of those posts for which they are peculiarly fitted—as teachers or maternity doctors—although it is against the law to bar women from any public activity on the ground of marriage. He cheats unemployed women out of their unemployment insurance more craftily and brutally than he cheats his fellow-men. Instead of realizing that the competition of women in industry and the professions is a competition of population pressure rather than of sex, he seeks by every means in his power to drive woman back to matrimonial dependence and an existence on less than half a miserably inadequate income; and then he mocks at her when she claims the right to stem the inevitable torrent of children whose advent will but aggravate man’s difficulties as well as her own. But worse than all the sniping is the smoke-screen of propaganda. While feminists have, in a large measure, stayed their hand, anybody who has anything abusive to say of women, whether ancient or modern, can command a vast public in the popular press and a ready agreement from the average publisher.

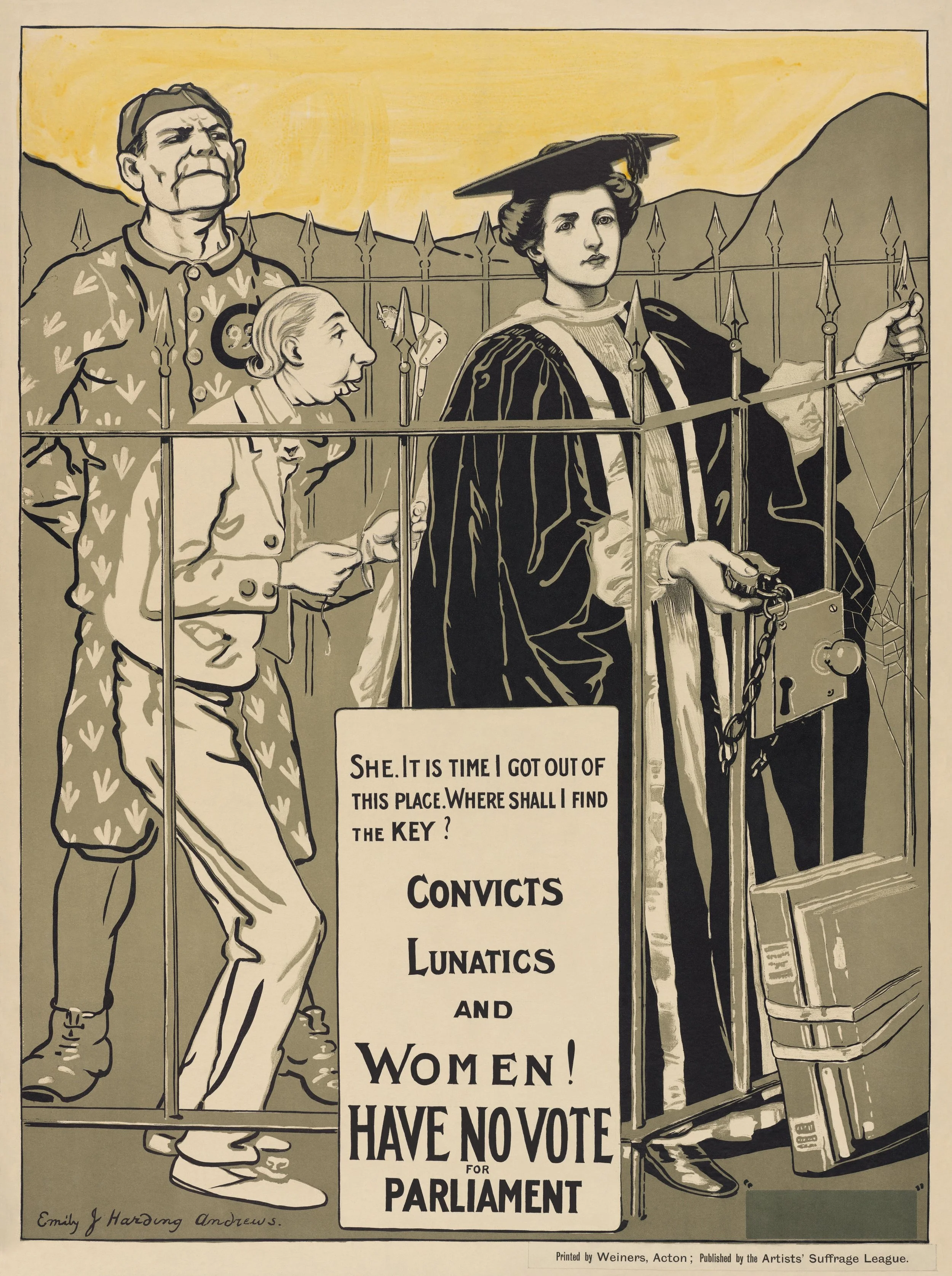

She. It is Time I Got Out of This Place. Where Shall I Find The Key? Convicts, Lunatics, and Women! Have No Vote for Parliament. (ca. 1907-1918)

It is a very insidious propaganda. Thus the fashion-papers tell us that grandmamma’s ways are coming back into their own; elsewhere we are flattered for the frank honesty of the modern girl and then warned not to ask for equal pay or opportunity.[1] Again, we hear that woman, like the Labour Party when in office, has done nothing with the opportunities given her by the vote; or that the country rejected the women candidates wholesale. This, regardless of the fact that the steady increase of the Labour poll has been due in great part to the votes and more to the organization and propaganda of large numbers of intelligent working women who know not only what they want, but how to get it. They are backed now by many of the middle-class women who were young enough to be revolted by war politics in 1914, and are old enough to claim their citizenship in 1924. Hundreds of thousands of others, now between twenty and thirty, mothers, professional and working women, will make themselves heard before long. To them, the principle of feminine equality is as natural as drawing breath—they are neither oppressed by tradition nor worn by rebellion. I venture to think that, had the Labour Party machine been less dominated by the masculine perspective, to which the equal franchise bill was a matter of secondary importance, they would not have lost so heavily in the 1924 election. Votes for women at 21 would have greatly increased the poll of many Labour candidates. I have seen young mothers almost sobbing outside the polling-station on polling-day because they had no vote to cast for the future of themselves and their children. As for the defeat of women candidates, everybody, including the leader-writers who spread the adverse propaganda, knew perfectly well that the majority of them stood in constituencies where even a man of their party would not have had the ghost of a chance. Here again Jason at headquarters displayed his well-known chivalry.

It is no part of my thesis to maintain that women display their feminism in proportion as they vote for any particular political party—Labour, for example. But I do suggest that it is the progressive working woman rather than the woman of the middle class who will in the future make the most important contribution to the thought of feminism and to a solution of our practical difficulties. One of the most inveterate anti-feminists, the author of Lysistrata, as an avowed anti-democrat, has based his thesis and his strictures on observations that do not go beyond the bounds of upper- and middle-class people, barely even beyond the bounds of the night club or the suburban dance-hall. In his eyes we are to blame for everything. Our worst crime is to “blaspheme life and man”; our next, not to have prevented food being put into tins; our next, to have adhered faithfully to that ascetic view of life and sex so firmly instilled into us by medieval monks and bullying Puritan fathers and brothers. We are to blame for the industrial revolution in that we let weaving, spinning, milling, and baking go out of our hands. We are to blame for the iniquities of doctors in that we did not maintain our position as the dispensers of healing potions and simples. We are to blame in that we have not learned to bring forth our children without pain, those children whose brows bear the marks of obstetric instruments that were used to spare their mothers, and whose lips have not been laid to those inhuman mothers’ breasts. (There are no scars of war, O Jason!) Where is salvation for us, and how shall we rid us of the burden of our iniquity? We who have waxed so arrogant that we have even aspired to let science build our children outside their mothers’ bodies must humble ourselves once more and take upon us the whole duty of woman. We must use our votes to restore aristocracy[2] and take the food out of tins; spin and weave, no doubt, the while we nurse and bear our yearly child, delivering it over to infanticide when necessary, since birth-control is artificial and displeasing to the male. In our leisure moments—of which, doubtless, we shall find many under this humane régime—we are to discover by what means of diet, or exercise it may be, we can fulfil our maternal functions with pleasure instead of suffering.

A joke, you say? No, no, my poor Medea, it is a man called Rousseau, risen from the dead. Not long ago he preached this sort of thing to women who pinched their waists and wore a dozen petticoats. They were not educated enough to follow Voltaire, so they listened to what Rousseau called the Voice of Nature. Soon thereafter, they found they were being abused for being less civilized, more ape-like than the male, irrational and unsuited to take a part in public life. So they tried again, poor things, and then there was an awful thing called the Industrial Revolution, and the food got into tins. They may be pardoned, as may all of us, if at this point they became a little bewildered. Some people blamed science, some civilization, some the meat-trusts and the millers, but the true culprit, as ever, was Woman. A thousand voices cried her down—she hadn’t enough children; she had too many; she was an ape; she was a dressed-up doll; she was a Puritan; she was an immoral minx; she was uneducated; they had taught her too much. Her pinched waist was formerly abused—now it was her slim and boyish body. Eminent surgeons[3] committed themselves to the view that the boyish figure with its pliable rubber bust-bodices and corselets would be the ruin of the race, that race which had been superbly undegenerate through four centuries of armour-plate corset and eighteen-inch waists, that race which, then or now, can hardly compete in toughness with the Chinese, among whom the boyish figure has been for centuries the ideal, and whose women cannot conceivably be accused of shirking any of the responsibilities of maternity. Others told us that the woman-doctor has no nerve to tend confinements, and conveniently forgot that, since the world began, and until quite modern times, it is women who have ministered to one another in that agony which now as in the past is the lot of every mother. Is there truth in the words of Jason? Is there truth or justice in the passion of Medea? Let us not ask the protagonists, but let us summon the inquiring intelligence of Hypatia to find us a way out of the intolerable tangle in which their quarrelling has landed us.

-

[1] Lovat Fraser in a cunning article in The Sunday Pictorial, January 4, 1925.

[2] An ingenious method of accomplishing this suggests itself. Since women do not sit in the House of Lords, suppose that all Peers’ wives, following the example of the Duchess of Atholl, stand for Parliament where their husbands have estates. This would obviate the necessity, now felt by Conservatives, of restoring the veto of the House of Lords.

[3] Sir Arbuthnot Lane, for whom I have hitherto entertained an entirely unqualified admiration, in a recent article. Vide The Weekly Dispatch, December 28.